Introduction

If we think about our home networks, we likely have more Internet of Things (IoT) and Operational Technology (OT) devices than traditional computers, and within enterprise networks these devices perform critical roles in security systems, building controls, manufacturing sensors and healthcare.

University College London (UCL) and the Institut national de recherche en sciences et technologies du numérique (Inria) have been collaborating on research into the security of these devices for some time. Using a large IoT testbed these organizations uncovered serious anomalies in the DNS behavior of these devices.

In the DNS world, IoT devices came to prominence in 2016 with the attack on Dyn, a major provider of DNS services. They suffered a massive distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack, disrupting access to major websites including Twitter, Spotify, Reddit, GitHub and Netflix. The attack was powered by the Mirai botnet, which hijacked thousands of insecure IoT devices. IoT botnet activity continues, as recently highlighted by Brian Krebs’ article on the Kimwolf Botnet.1

While the “normal” (bad) DNS behavior of devices and those of compromised devices are not directly related, there is an overlap in some of the mitigations that points us to how we can move toward security-by-design in the manufacture and operations of IoT. This article discusses the risks identified by the research, how these might be addressed and the mitigations network operators can use.

Research Results

Using a large-scale IoT testbed, researchers at UCL and Inria analyzed 30 consumer IoT devices across categories such as cameras, doorbells, lights, sensors and medical devices.2 The methodology included passive traffic inspection and active testing.

Key findings included:

- No support for Encrypted DNS (DoH/DoT/DoQ): This means queries would be visible, which could lead to device fingerprinting and privacy issues.

- Hardcoded DNS Resolvers: Some devices ignored network DNS resolver settings and instead used well-known open DNS resolvers such as Google’s 8.8.8.8 DNS service. If this is permitted on a network, it would bypass local security controls or those a home network service provider is delivering to its customers. Conversely, if a device has a hardcoded resolver as shipped it may not work if that open resolver is blocked due to network policy.

- Poor Source Randomization: Devices used predictable source ports and transaction IDs, increasing the risk of cache poisoning and spoofed responses.

- No DNSSEC Adoption: None of the devices validated DNS responses, making them vulnerable to spoofing.

- Time to Live (TTL) Mismanagement: Devices ignored TTL values, causing erratic query behavior and inefficiencies.

- Fragmentation Issues: Limited support for Extension Mechanisms for DNS (EDNS0) UDP message size led to inefficient handling of large DNS queries that testing showed could lead to operational issues.

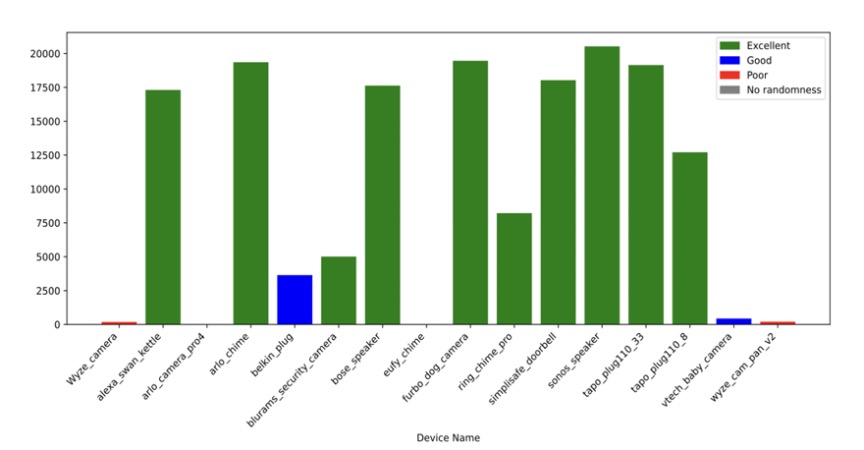

Andrew Losty, a PhD student at UCL and one of the Internet Draft authors, presented research findings at RIPE 91,3 and the slides and recording of this are available here. As one example, the following graph shows the lack of transaction ID randomization in some devices, making it more likely to accept a spoofed DNS response.

Figure 1. Transaction ID results

Risk Mitigations

Strengthening DNS Security in IoT Devices

To address the DNS-related vulnerabilities uncovered in the UCL and Inria research, we are working together on an Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Best Current Practice draft via the IoT working group. This is the logical place for this work as the DNS protocol is developed within the IETF and the IoT working group has a focus on the management and operations of the types of devices tested.

Manufacturers of IoT/OT devices need to ensure adherence to the following:

- Compliance to encrypted DNS standards such as DNS over TLS (DoT), DNS over HTTPS (DoH) or DNS over QUIC (DoQ) for enhanced privacy, security and compatibility

- Support for the configuration of DNS servers manually, via device management software, IPv6 router advertisements, DHCP and discovery of designated resolver standards; devices should not have hardcoded resolvers for security and operational reasons.

- DNS source port and transaction ID randomization to reduce the risk of spoofed responses being accepted by the device

- Devices honoring DNS record TTL values, perhaps with a maximum for operational reasons, with manufacturers also setting management domain records to appropriate values

- Support for EDNS0 to improve device efficiency and not impact the operation of a device when responses exceed the traditional 512 byte UDP limit

- Develop support for DNSSEC, for instance checking the Authenticated Data bit in resolvers’ responses; manufacturers must sign their public zones used for device management and any data collection

More details can be found in the Internet Draft IoT DNS Security and Privacy Guidelines.4

Network Operator Mitigations

There are broadly two network operator types where IoT devices are deployed: service providers of consumer networks, for instance the networks we have at home, and organizations managing their own infrastructure. The main difference from a DNS perspective is that a consumer may use any DNS server, while an organization managing its own network should restrict DNS traffic to its own resolvers for security and policy reasons. In the consumer case it is advantageous for the end user to use the provider’s resolvers and most home networks would do this in any case.

Operators can restrict networks where IoT devices are deployed to only query domain names in management zones via Protective DNS.5 They can see what these are via analyzing DNS traffic, but we are calling on manufacturers to provide these, either by simply publishing them or via the use of the Manufacturer Usage Description (MUD) specification.6

This means that the networks would be operated on a Zero Trust DNS basis, along the lines of Microsoft’s Zero Trust DNS.7 This mitigates against devices being compromised, including in the supply chain.

Where DNS resolution needs to be more open, such as on consumer networks where any device can be deployed, the network operator can still use Protective DNS to block malicious domains used in the compromise or control of devices.

Operators should have resolvers validate responses via DNSSEC in any case, but specifically in the context of IoT it will allow devices to take advantage of manufacturers signing their public zones.

Regulation Improvements

Having improved standards that are enforced through certification will move us to a more secure-by-design paradigm.

While organizations such as ETSI, ISO/IEC, ITU-T and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have varying amounts of guidance on DNS security as it applies to IoT/OT, there are certainly gaps here. Developing a Best Current Practice Draft within the IETF IoT Operations working group will allow this to be referenced by organizations such as ETSI where work for the certification of IoT devices is ongoing.

As an example, provision 5.5-5 in the ETSI EN 303 645 V3.1.3 (2024-09) standard states “Consumer IoT device functionality that allows security-relevant changes in configuration via a network interface shall only be accessible after authentication. The exception is for network service protocols that are relied upon by the consumer IoT device and where the manufacturer cannot guarantee what configuration will be required for the consumer IoT device to operate.” One of the exceptions is for DNS.

This should not exist as a blanket exemption. Rather than manufacturers complying with just device security, standards should consider the wider security context, especially where it is in same manufacturer’s control. The ETSI standard states “To increase security, multi-factor authentication, such as use of a password plus OTP procedure, can be used to better protect the consumer IoT device or an associated service.” The multi-factor authentication service and infrastructure is outside of the device and the manufacturer’s control, whereas public management domains can be cryptographically signed, and devices can check if this has been verified—all within one manufacturer’s control.

The natural tension in this is keeping regulation generic enough to allow for developments in tech and to document intent or outcomes versus being protocol specific. This is where IETF Drafts and RFCs can be referenced to bridge the gap and mean standards bodies do not need to maintain specific detail on protocol compliance.

Conclusion

The message can be boiled down to manufacturers following the DNS standards we already have (as detailed in the Draft we published), helping operators by providing management domain information to secure networks, pushing the use of PKI to manage devices in the form of DNSSEC (we do this with certs) and regulators referencing this in their standards.

As we continue to work on the Draft, turning research findings into actionable guidelines, we invite you to join the conversation via the IETF whether you’re a device manufacturer, network operator or security professional.

If you are a network operator or security professional there are some practices in the Draft that will improve network security and you can help practically, for instance ask the manufacturers of the devices you use to let you know the management domains names so you can lock down communications to only those domains via Protective DNS.

The Internet-Draft discussed in this blog has been authored by Jim Mozley (Infoblox), Abhishek Mishra (Inria), Andrew Losty (UCL), Anna Maria Mandalari (UCL) and Mathieu Cunche (INSA-Lyon & Inria).

Footnotes

- The Kimwolf Botnet is Stalking Your Local Network, Krebs, Brian, Krebs on Security, January 2, 2026. https://krebsonsecurity.com/2026/01/the-kimwolf-botnet-is-stalking-your-local-network/

- Towards Operational and Security Best Practices for DNS in the Internet of Things, Losty, Andrew, Mishra, Abhishek, Cunche, Mathieu, Mandalari, Anna, ANRW 2025 – Applied Networking Research Workshop, July 2025. https://hal.science/hal-05110445/

- Towards Operational and Security Best Practices for DNS in the Internet of Things (RIPE 91 presentation), Losty, Andrew, Réseaux IP Européens (RIPE), October 24, 2025. https://ripe91.ripe.net/programme/meeting-plan/sessions/52/TCAFQK/

- IoT DNS Security and Privacy Guidelines, Mishra, Abhishek, Losty, Andrew, Mandalari, Anna, Mozley, Jim, Cunche, Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), January 23, 2026. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-iotops-iot-dns-guidelines/

- What is Protective DNS (PDNS)? Infoblox. https://www.infoblox.com/dns-security-resource-center/dns-security-faq/what-is-protective-dns-pdns/

- Manufacturer Usage Description Specification (RFC8250), Lear, Eliot, Droms, Ralph, Romascanu, Dan, Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), March 2019. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc8520

- Zero Trust DNS, Microsoft. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/security/operating-system-security/network-security/zero-trust-dns/