Authors: Maël Le Touz and John Wòjcik

Introduction: Flooding the world

The scam industry has undergone massive transformations over the last decade. The cliché image of the once-iconic Nigerian prince duping Westerners from a local cybercafé is now passé. Western Africa is still a hotbed for digital fraud operations, but it has been superseded in both scale and efficiency by hundreds of industrial-scale scam centres now scattered throughout Southeast Asia.

Over the past decade major Chinese-speaking criminal groups have managed to infiltrate a growing number of countries in Southeast Asia, securing vast amounts of land to build cities and special economic zones dedicated to crime operations. They have established sophisticated global money laundering and human trafficking networks dedicated to staffing these operations with tens of thousands of slave workers brought in from countries around the world and forced to scam from bases in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines, and elsewhere.

In this paper, we examine one of the key drivers of the ongoing sha zhu pan (pig butchering) epidemic: service providers supplying criminal networks with the tools, infrastructure, and expertise that enable their operations to scale. These providers have created a robust, booming pig butchering-as-a-service (PBaaS) economy—not all that different from well-known malware and phishing-as-a-service (MaaS and PhaaS) models, that fuel cybercrime around the world.

Here, we delve into PBaaS, discussing two specific actors in detail. The first offers customers access to all the material they need to run social engineering operations at the heart of these crimes, while the second offers the technical platforms necessary to manage the scams and their agents. We used underground forums to learn the specifics of the threat actor’s offerings, including everything from stolen credentials to SIM cards. We purchased access to a management platform to get an inside look at how they scale. This very same platform was used by Chinese criminals arrested in the United States in February 2025 for defrauding victims of over US$13M.1 In combination, these two actors demonstrate that the tools to run pig butchering scams at scale are now a commodity. Where it was once remarkable that a victim could lose US$250k or more, losses of this scale are now commonplace. Law enforcement and defenders need to look at new methods to tackle this exploding criminal ecosystem.

The Tools of the Trade

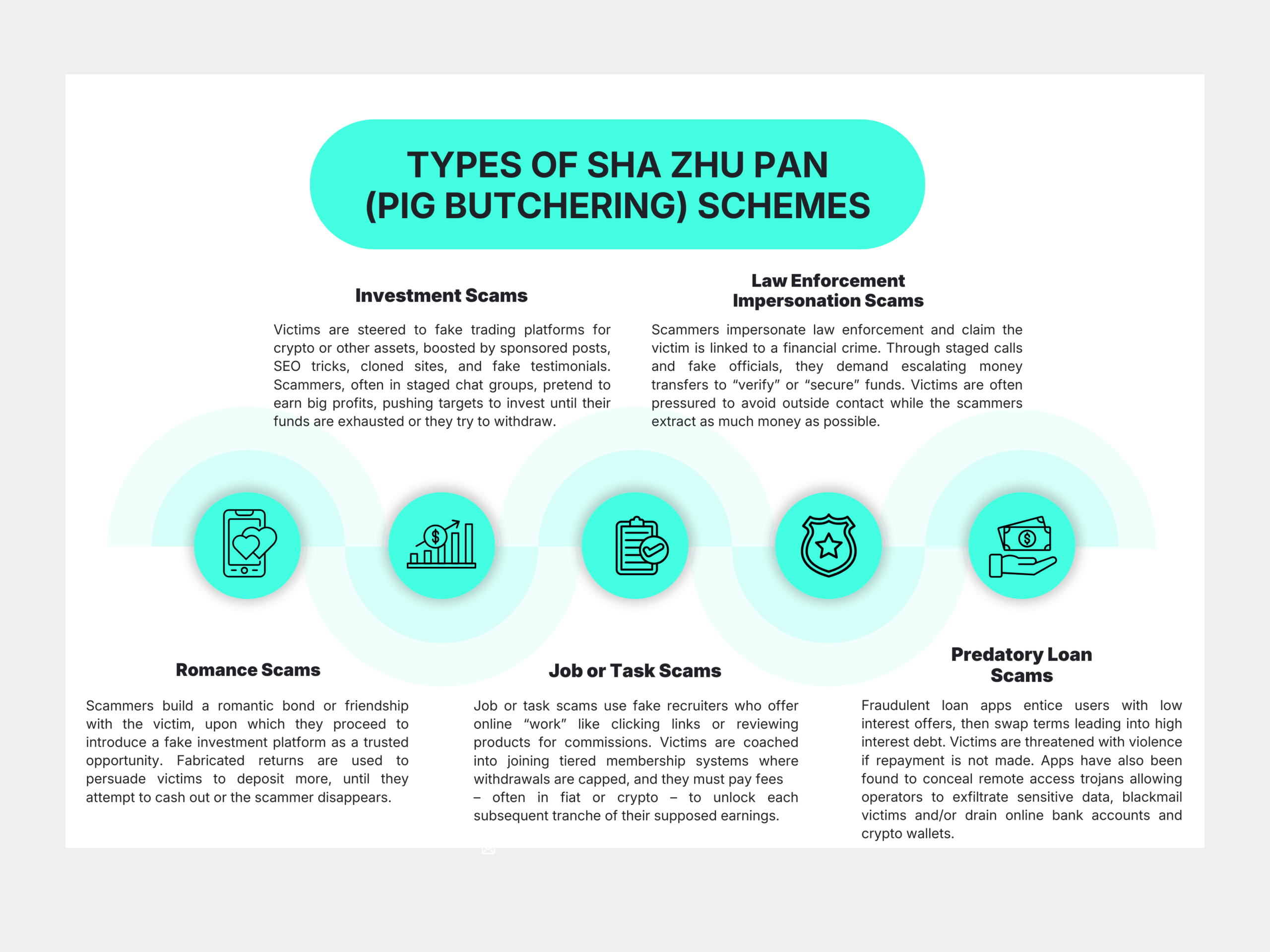

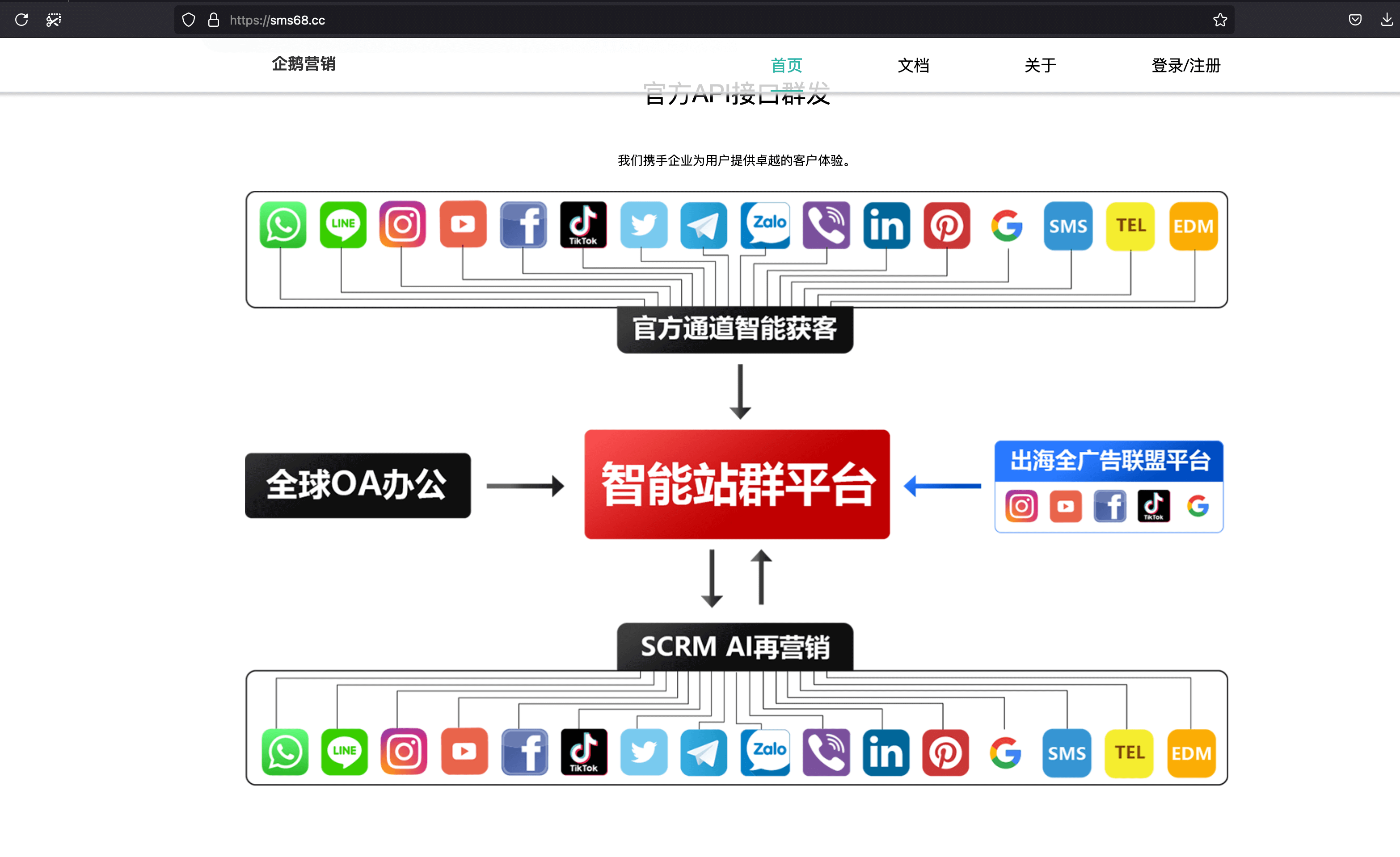

As shown below in Figure 1, sha zhu pan operations, often called pig butchering schemes, have evolved and now include a broad range of common typologies. From romance and investment scams to law enforcement impersonation and job or task scams, the tools necessary to run these operations are readily available on specific marketplaces.

Figure 1. Common types of sha zhu pan schemes running out of Southeast Asia. Elaboration based on UNODC (2025).

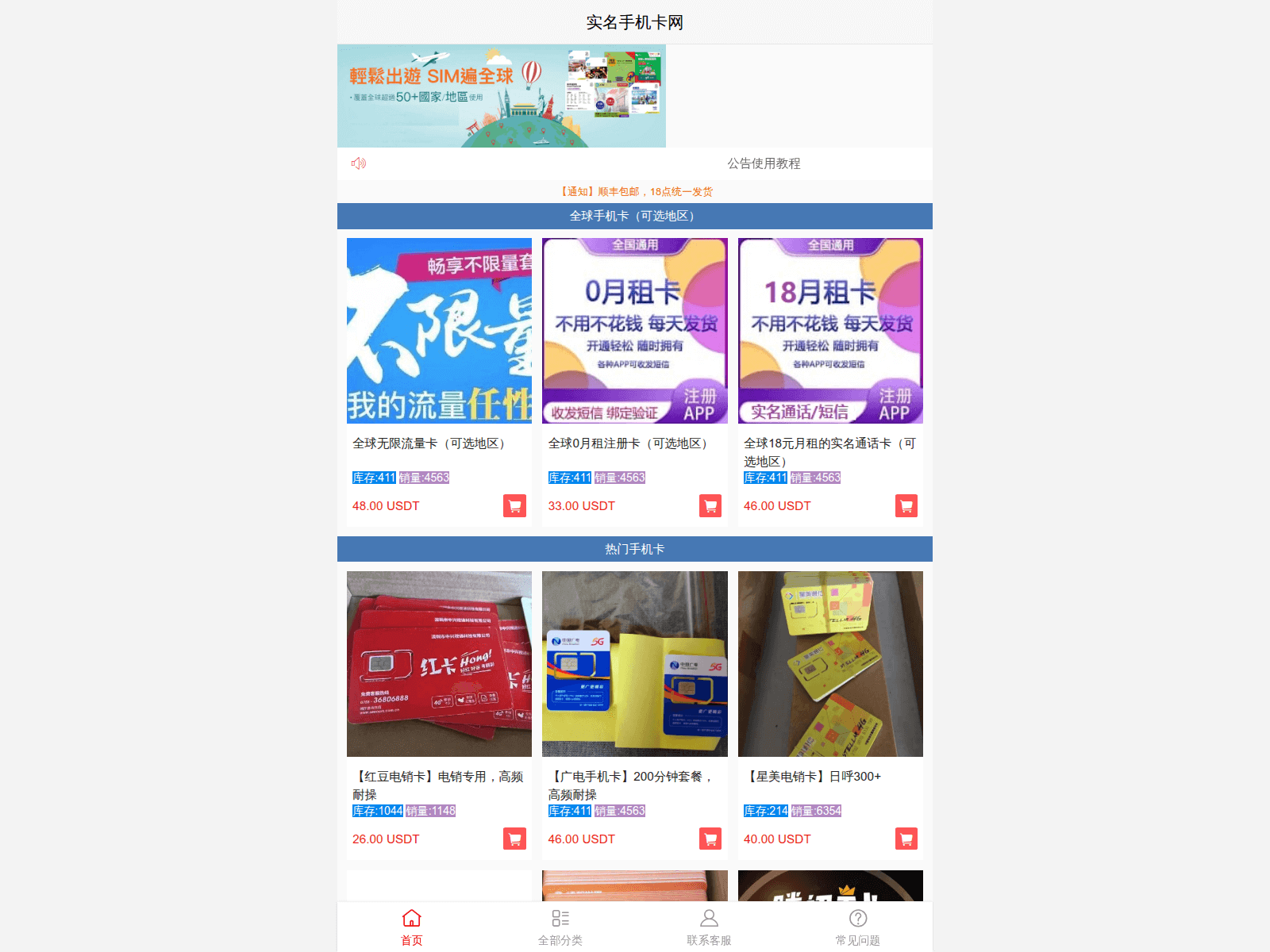

Scammers need communication equipment and compelling scripts for social engineering, access to bank accounts, disposable devices, internet, social media accounts, profiles and content, and a website to direct their targets to. They also need a reliable way to quickly launder stolen funds and cryptocurrencies, and to move their wealth out of reach of law enforcement. This includes utilizing pre-registered SIM cards, fake identities and stolen social media accounts, smuggled Starlink satellites, and a rigged online investment platform. That said, while these various tools and components can be purchased, there are many, many pieces.

Like baowangs or white labels for online gambling,2 an entire ecosystem of service providers has quietly proliferated online in Southeast Asia, offering full packages and fraud kits containing everything required to set up shop and launch scalable online scam operations. This allows easy turnkey-like access to enter the scam trade just like phishing and malware service providers have offered for years. We have been able to track down multiple groups operating in this space and servicing criminal networks with a variety of PBaaS solutions.

Introducing the “Penguin Account Store”

We have identified one such group in the market using several names including Heavenly Alliance, Overseas Alliance, and Penguin Account Store (in Chinese). We’ll refer to them simply as ‘Penguin’ moving forward.

The actor openly advertises and sells fraud kits, scam templates, and other solutions to cybercriminals seeking to run their own schemes. As is characteristic of Chinese-speaking crime groups, Penguin is loosely organized and operates through a crime-as-a-service model, making it difficult to distinguish core operators from copycats.

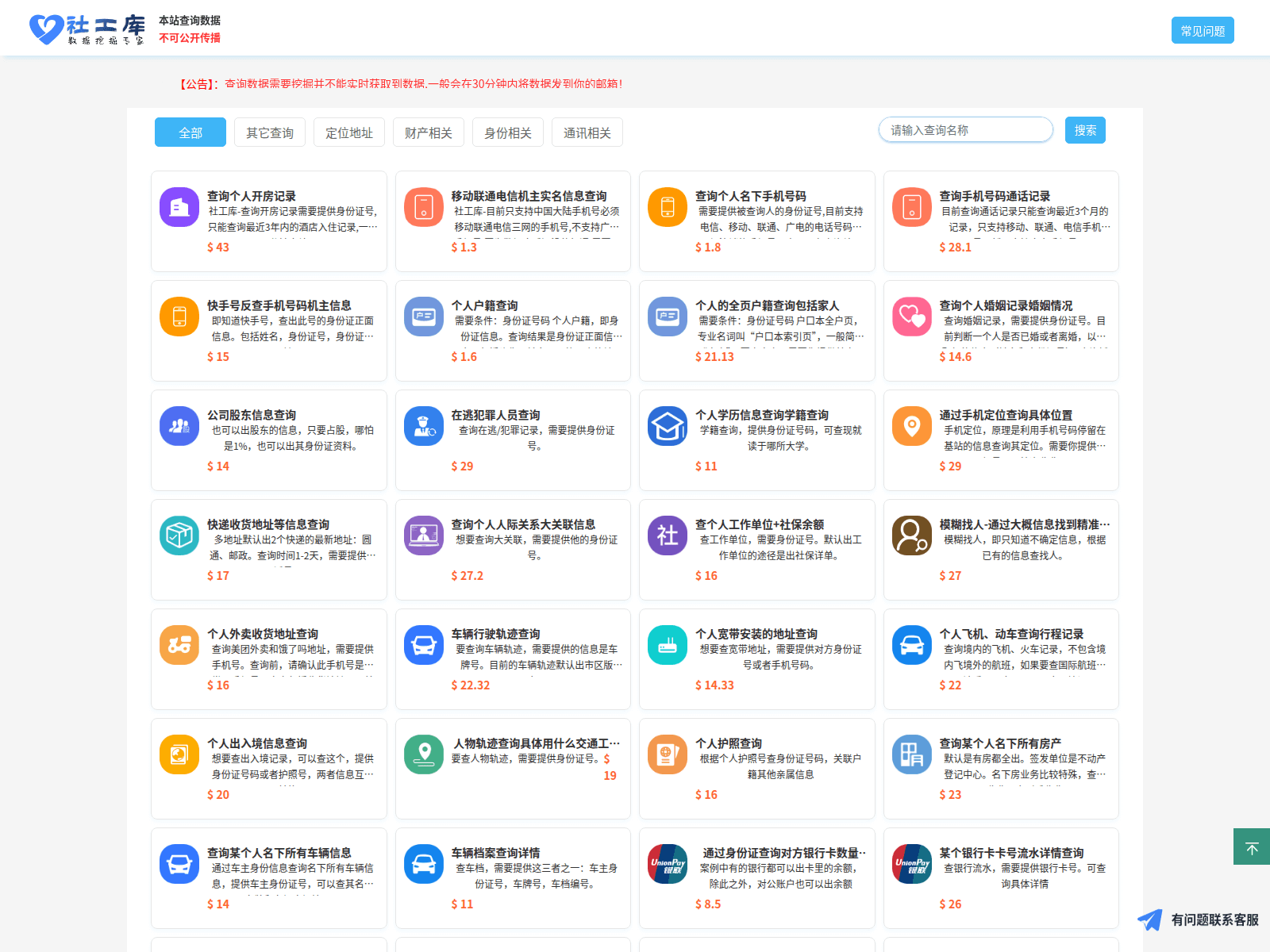

Penguin began with shè gōng kù (社工库), literally, a “social worker database.” This is a code word for the theft and resale of personally identifiable information (PII) belonging to Chinese citizens. This data is usually collected by state agencies and obtained via corruption or hacking.

Shè gōng kù data is extensive, often containing years of bank records and travel history, documentation of political leanings and information about relatives. The scammers leverage this info to identify and target wealthy victims. Personal data is also used to establish trust and enrich social engineering tactics. After all, who other than your bank would call with knowledge of your recent transactions? And who else could possibly know about your income records besides the government? Figure 2 shows a panel containing many offerings for personal and financial data that is available for sale.

Figure 2. Shè gōng kù panel operated by Penguin. It includes services such as “hotel booking history,” “criminal history,” “banking history,” and “relatives search.”

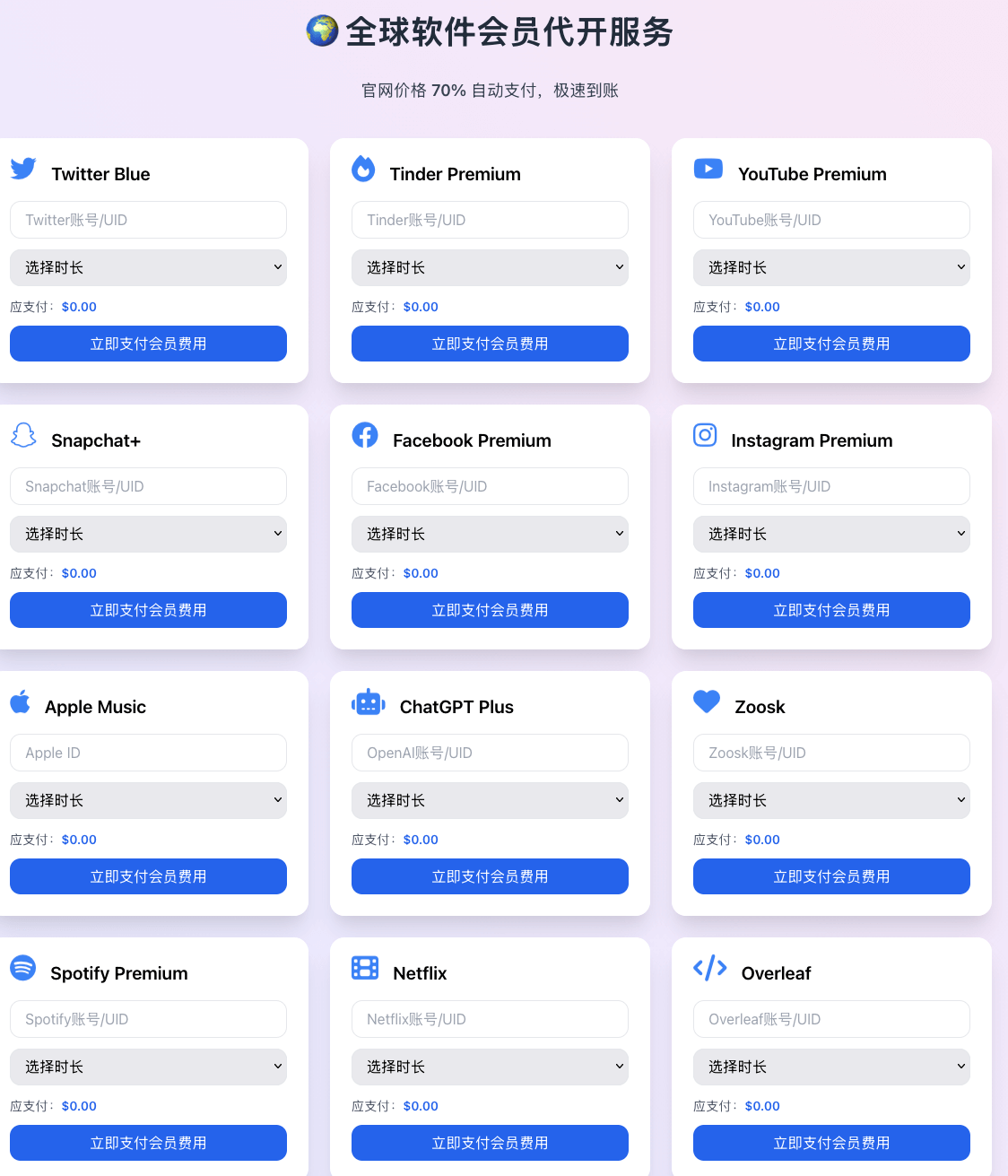

The group also sells account data from Western social media platforms, including Tinder and WhatsApp, as well as login information from sites like Adobe and Apple’s developer platforms. We show an example of the types of account information available for sale in Figure 3. The credentials they offer for sale are likely obtained through information stealers, but it is unknown whether they operate these or act as a broker for other threat actors. The prices are very affordable, with pre-registered social media accounts starting from just US$0.10 and increasing in value depending on the date of registration and authenticity.

Figure 3. Panel dedicated to stolen accounts on Western services

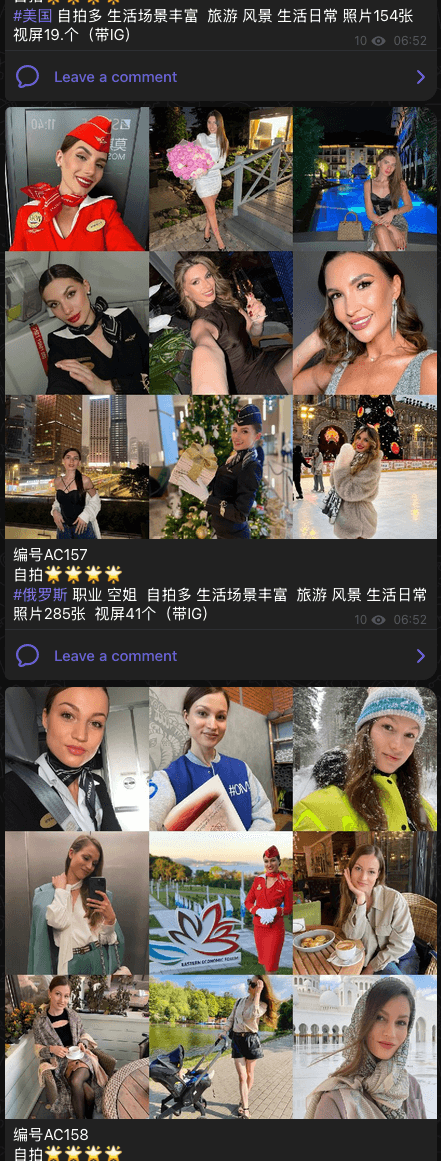

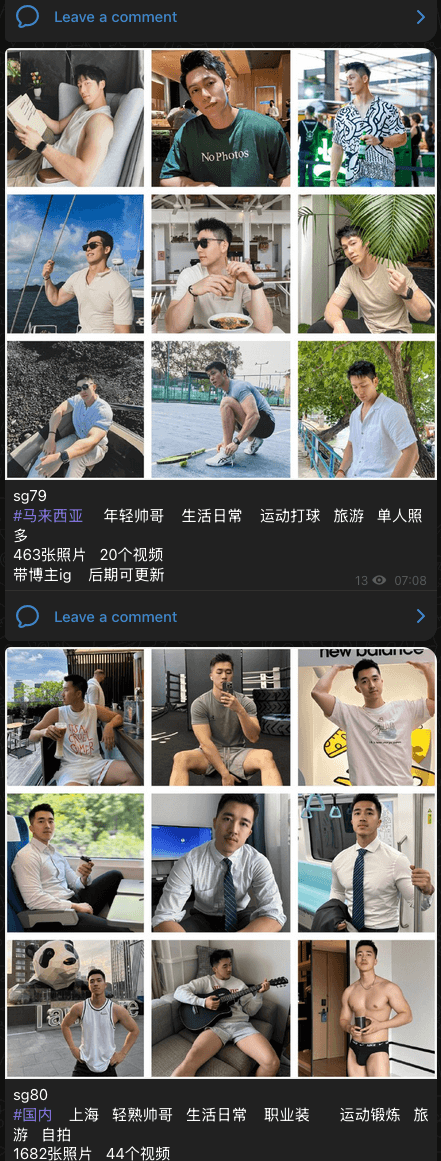

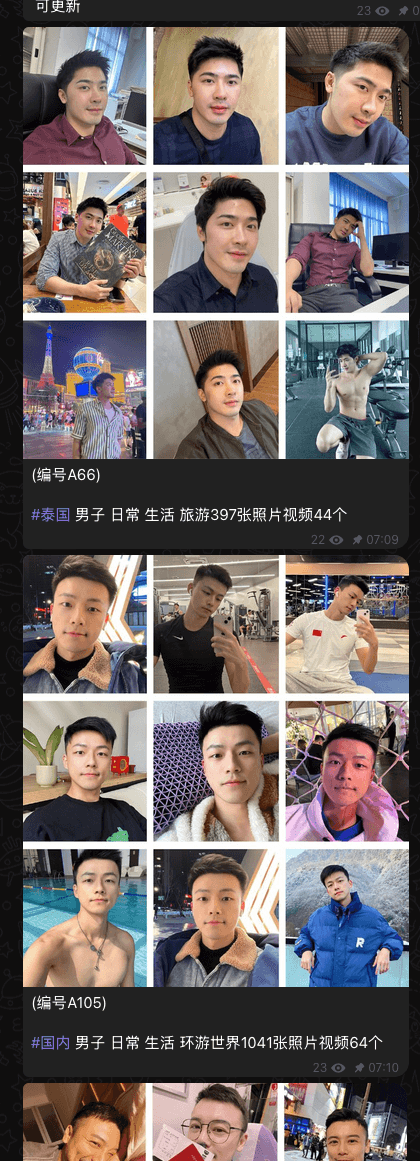

The threat actor’s current offerings include many other components necessary to run a large-scale pig butchering operation such as bulk pre-registered SIM cards, stolen social media accounts, 4G or 5G routers and IMSI catchers, “character sets” (人设套图) or packages of stolen pictures used to lure victims. These are often harvested from the same social media profile to ensure authenticity and allow the scammers to deploy these images in a variety of social engineering scenarios.

See Figures 4 and 5 for examples of some of the character sets for sale by Penguin.

Figure 4. “Character sets” offered for sale. Those pictures—stolen from social media—will be used by scammers.

Figure 5. The Penguin Account Store selling anonymous SIM cards and credit cards in bulk.

To further accelerate the scamming process and reduce manual tasks, Penguin even offers a Social Customer Relationship Management (SCRM) platform that they call “SCRM AI”. SCRM platforms were created to allow legitimate brands to centralize operations and streamline community management, but are increasingly abused by scam operators for mass account takeovers and automated victim engagement on social media. It is unknown how much AI is in the SCRM AI product; see Figure 6.

Figure 6. Advertisement for Penguin’s SCRM product, which hints at the use of AI.

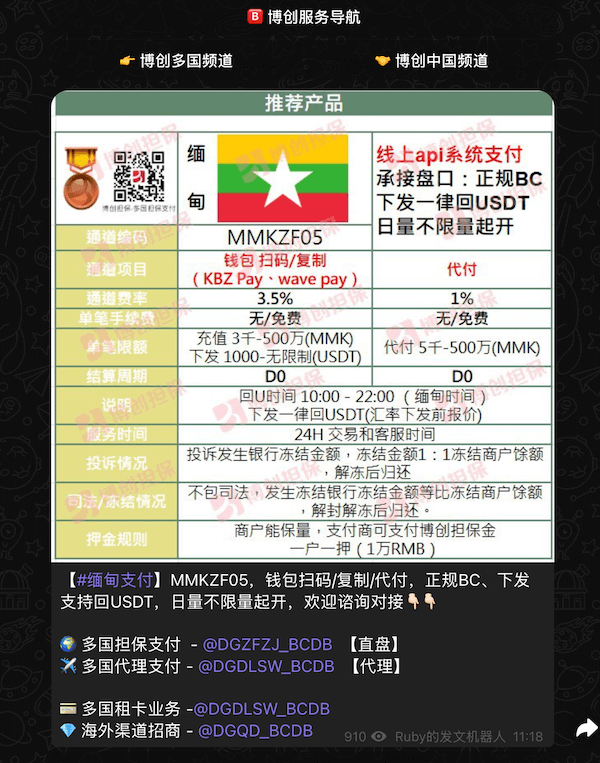

The threat actor also advertises BCD Pay, a payment processing platform. BCD Pay, which links directly to the Bochuang Guarantee (博创担保自), is an anonymous peer-to-peer (P2P) solution à la Huione, with deep roots in the illegal online gambling space. This company is mysterious; the only place where Bochuang has been mentioned publicly was a SiGMA trade show, a casino event sponsored by DB Gaming aka Vigorish Viper. See Figure 7.

Figure 7. Mention of a Bochuang booth at Sigma, a gambling trade show. On the right, a money mule offering their services from Myanmar on the Bochuang Telegram channel.

Despite all the tools offered by Penguin, scammers still need one thing: a platform they can direct victims to—the actual pig butchering website and fraud content. Such platforms are provided by different groups within the PBaaS economy.

UWORK Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

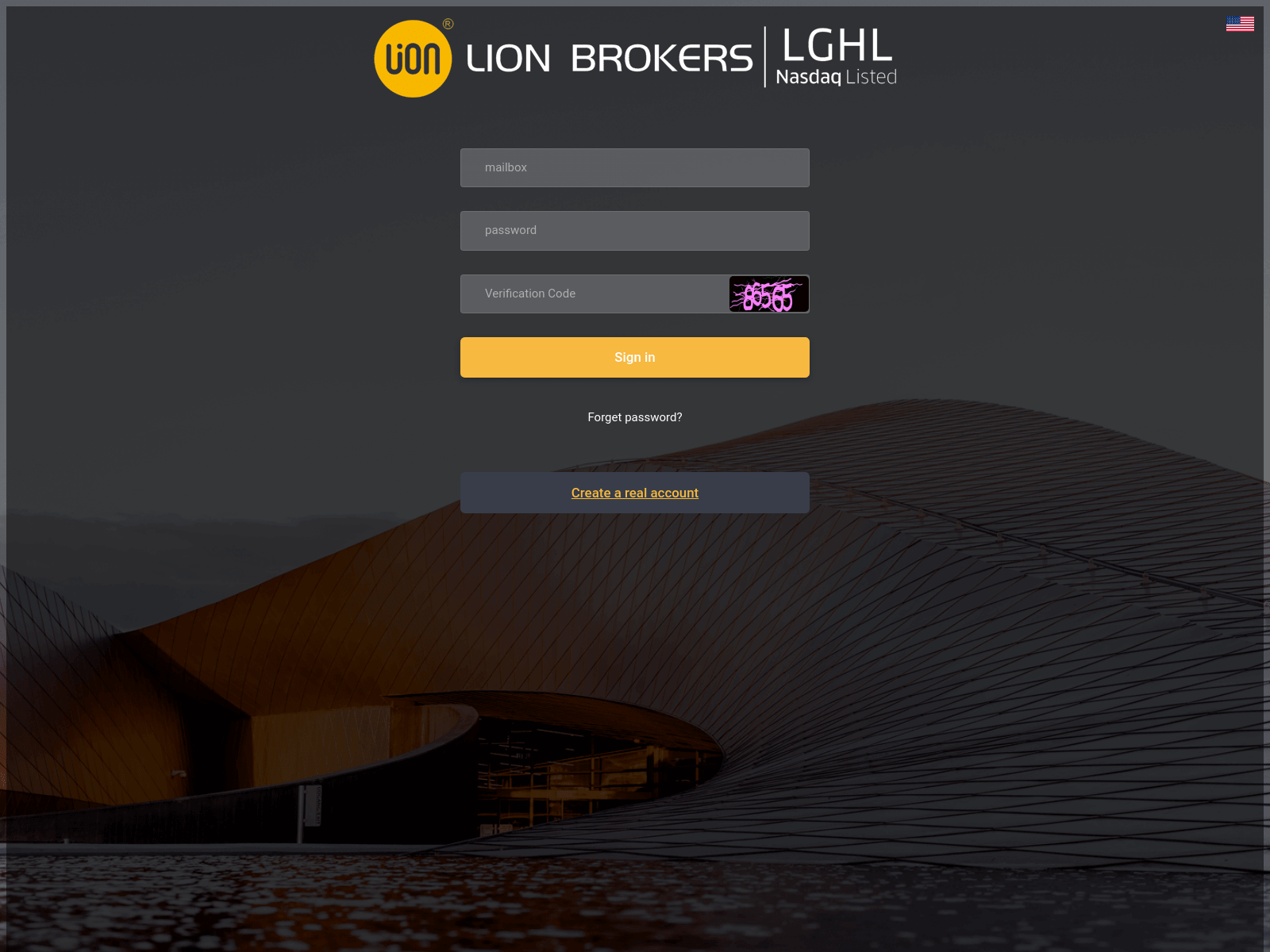

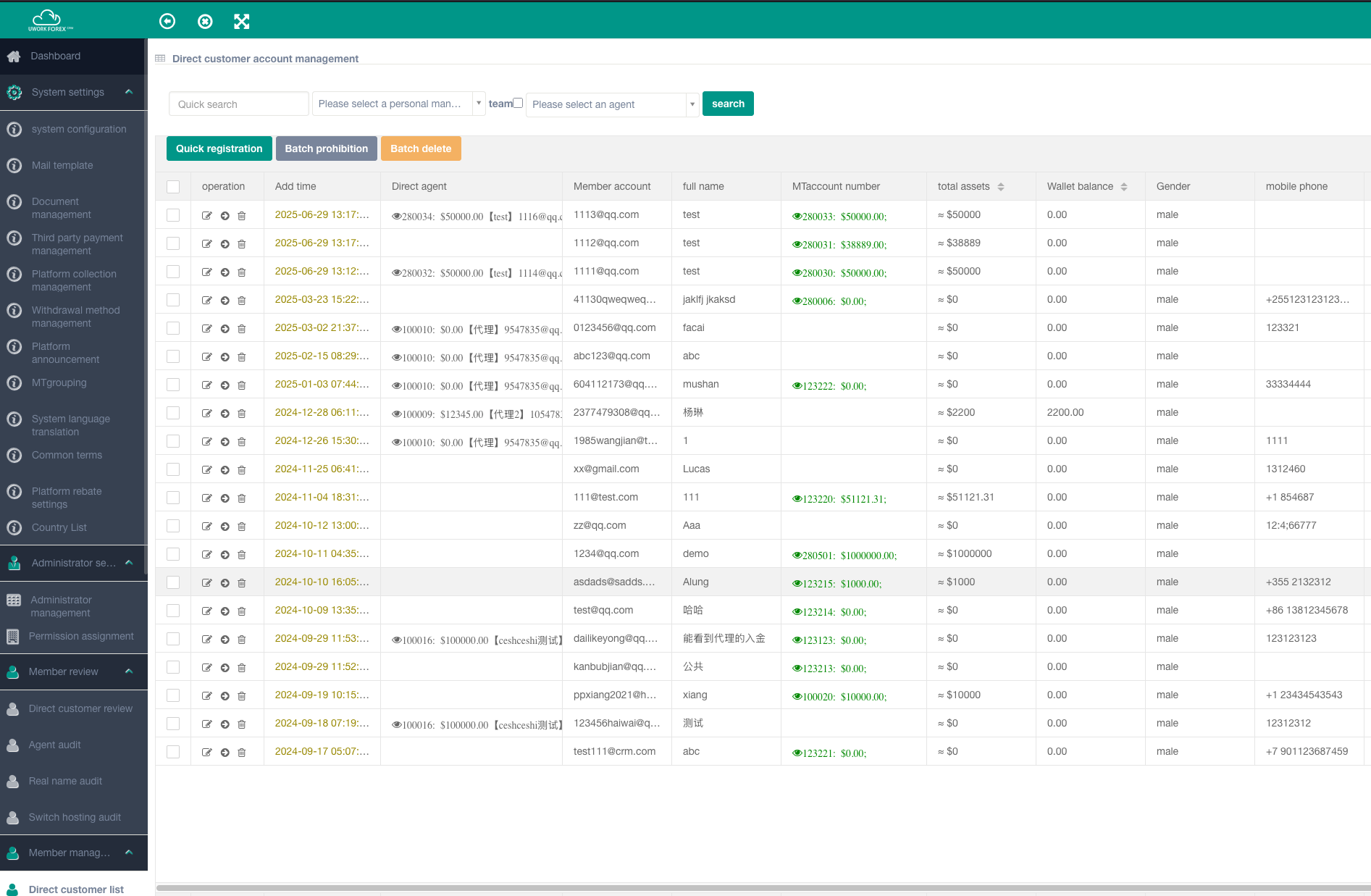

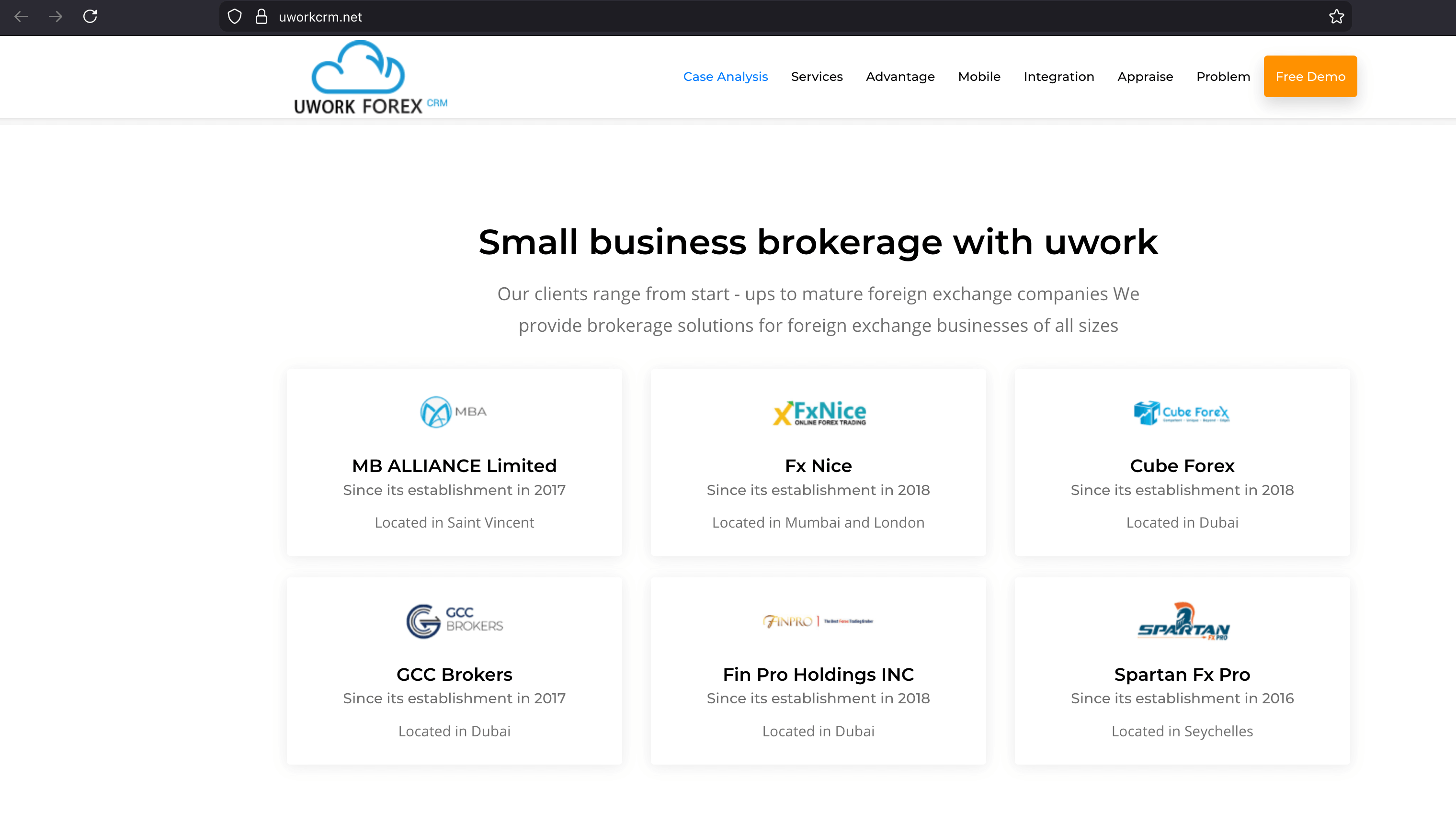

There are dozens of sellers advertising kits, on Telegram and other social media sites, that allow for content and agent management. These include customer relationship management (CRM) platforms that provide centralized control over several individual agents. We were able to acquire CRM access from one of these sellers, “UWORK,” whose products were leveraged by Chinese criminal actors to steal in excess of US$13M. According to a recently prosecuted case3,4 UWORK provided the template for lion-forex[.]com, known as Lion Brokers, a fake investment platform mentioned in the indictment; see Figure 8. The website queries resources from uworkcrm[.]com, a domain found in hundreds of other sha zhu pan websites. A large number of mobile app pages—offering both iOS and Android downloads—also use this CRM tool and domain.

Figure 8: Archived homepage of the lion-forex[.]com website showing a login to fake investment platform Lion Brokers. Accessed at: https://urlscan.io/result/32a23697-ebc8-473c-a44b-b2c456c26633/

During our analysis of UWORK, we found DNS signatures that allow us to track their activity. Furthermore, we were able to discover that the actor was operating from Taiwan, while their customers were located throughout Southeast Asia. Access to the CRM tool gave us a better understanding of how these PBaaS offerings work.

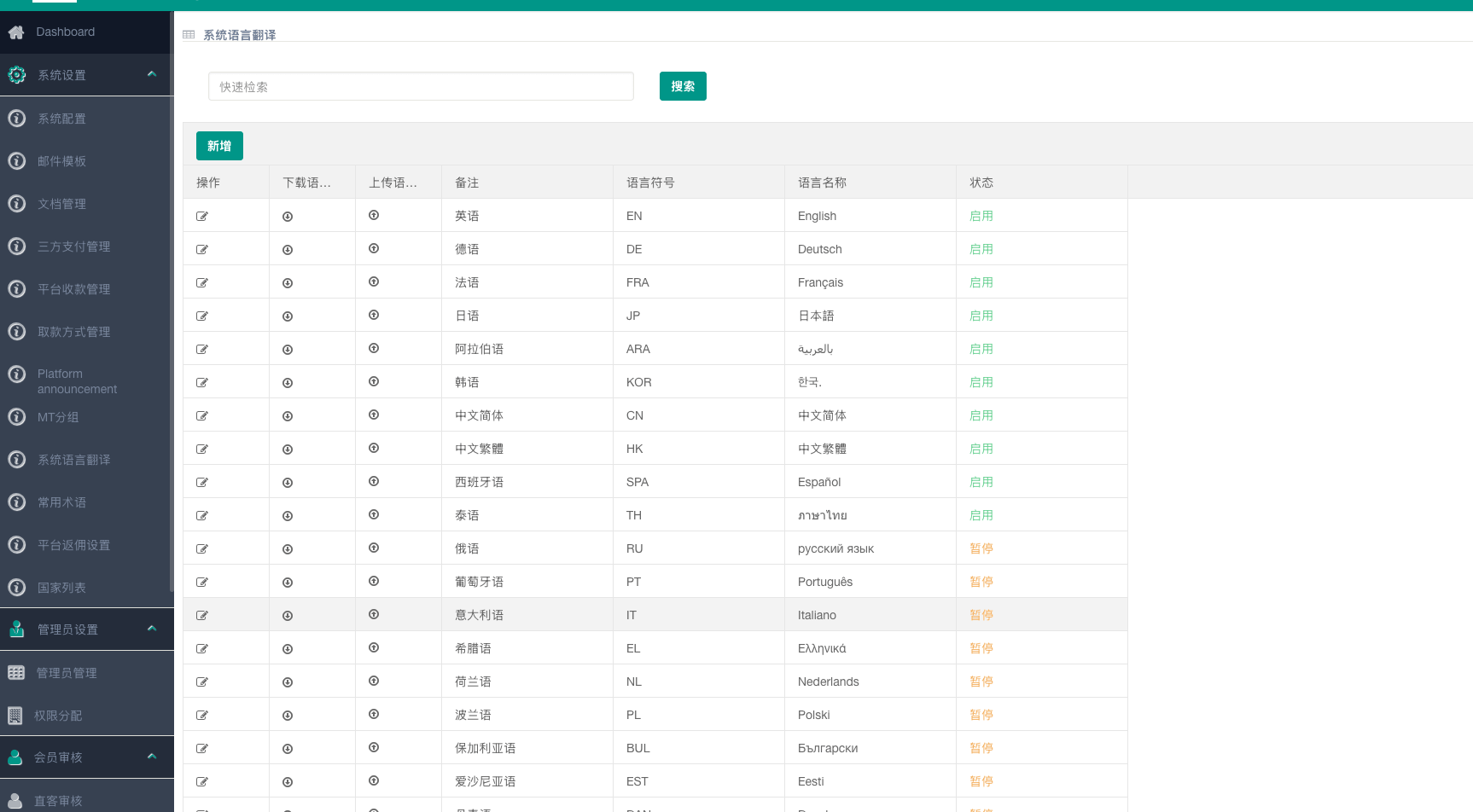

Using the Template Apps

After successfully logging into the CRM platform with credentials supplied by the seller, we were presented with an admin panel offering a variety of customization options and support for dozens of languages. Initial setup is a multi-step process, requesting the administrator to configure settings to interface with their email provider and their trading broker. The platform offers multiple pre-made templates, including those geared towards crypto, forex or gold investment. The resulting website can also be easily geofenced—i.e. restricted to IPs from certain countries—in an effort to avoid law enforcement takedowns in high-risk jurisdictions. Websites can be configured to interface with email and Telegram for automated customer contacts and updates. The icing on the cake? The platform’s Know Your Customer (KYC) panel requires victims to upload proof of their identity, just like on a real trading website. One can only imagine what will happen to that PII once it’s in the hands of these scammers.

When the website is up and running, the admin can create multiple profiles for the agents running the scams and set very precise rules. However, the admins don’t run the scams (interface with the victims)—this is done by “first-level agents,” possibly including forced labor.

First-level agents have very restricted access and can only perform basic operations on the victim accounts that they are handling. For example, if a victim deposits more than a threshold amount, the admin will be notified, and the money will be automatically transferred from the deposit account to one inaccessible by the first-level agent. This is likely designed to prevent first-level agents from keeping the money for themselves.

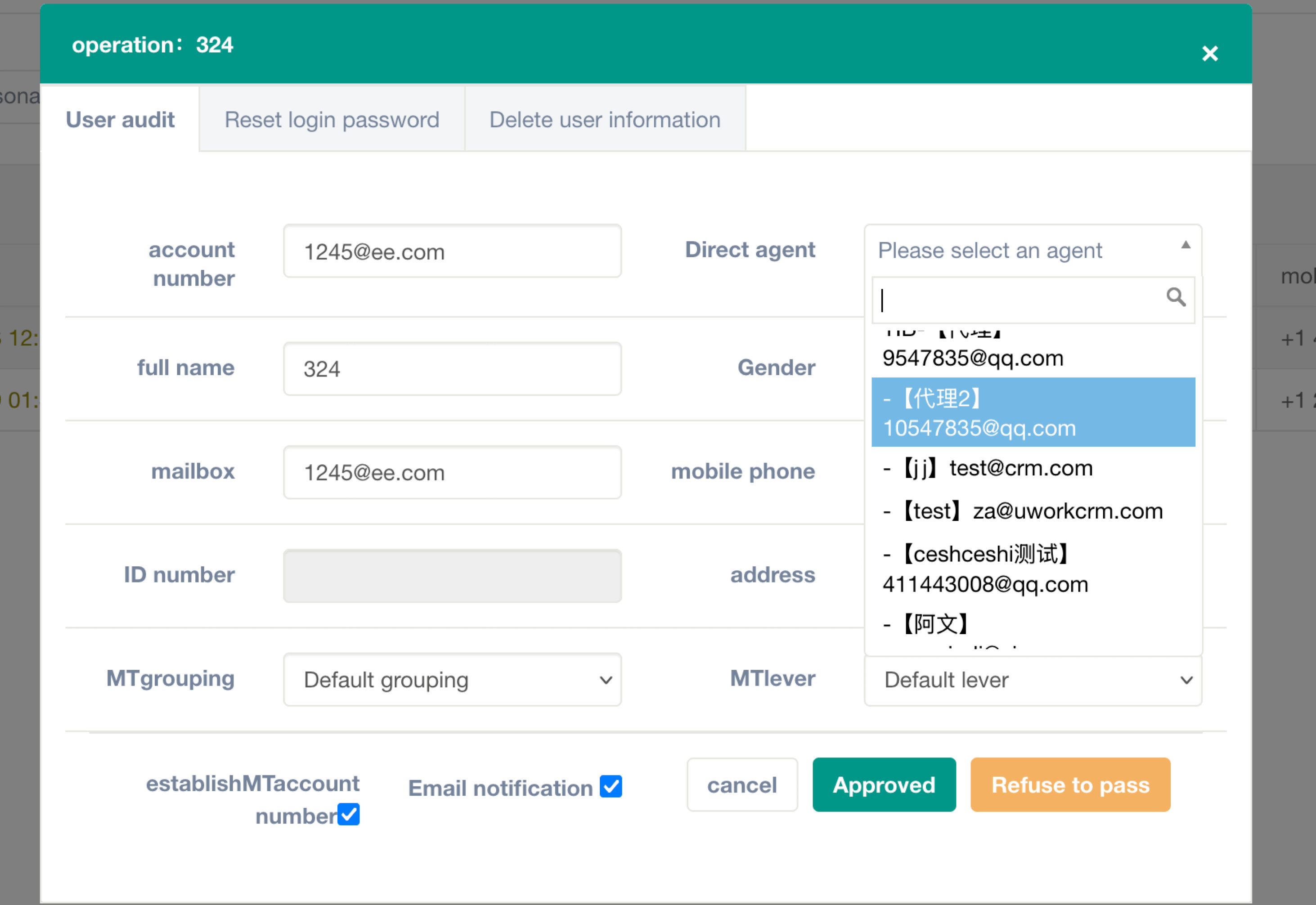

The administrators have access to multiple dashboards that display profitability metrics of the complete operation, broken down by each individual agent. They also enjoy a variety of tools at their fingertips to avoid detection, such as requiring admin review for user registration. Figures 9 and 10 show the panel used to add a new victim account to the website.

Figure 9. Admin panel from the same tool used by indicted criminals Jiao Jiao Liu et al., offering templates in over a dozen languages.

Figure 10. Panel to add a new victim account and assign them a direct agent.

The admin panel offers everything needed to run a pig butchering operation. Multiple email templates, user management, agent management, profitability metrics, as well as chat and email records. The management of agents is very complex, and agents can even be affiliates of one another.

Other Features of PBaaS

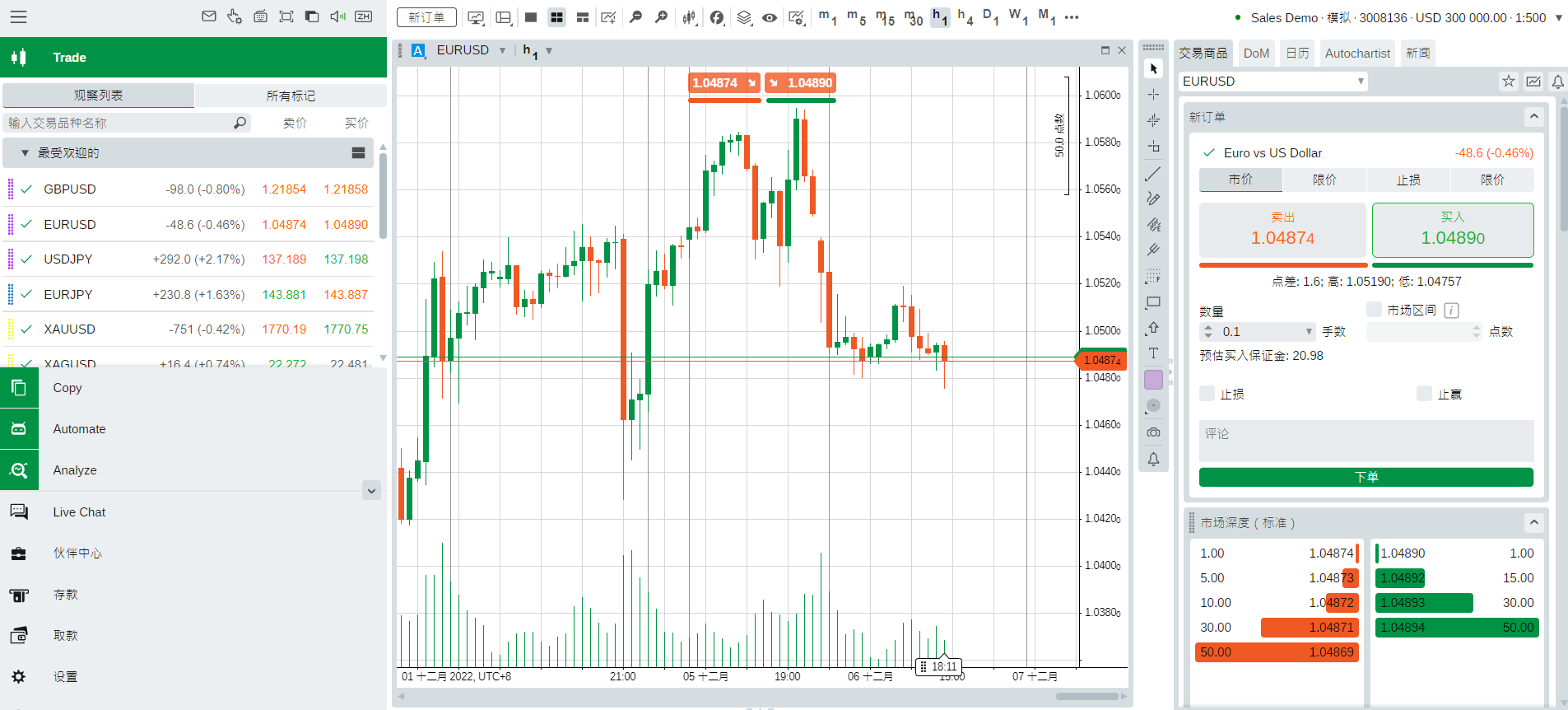

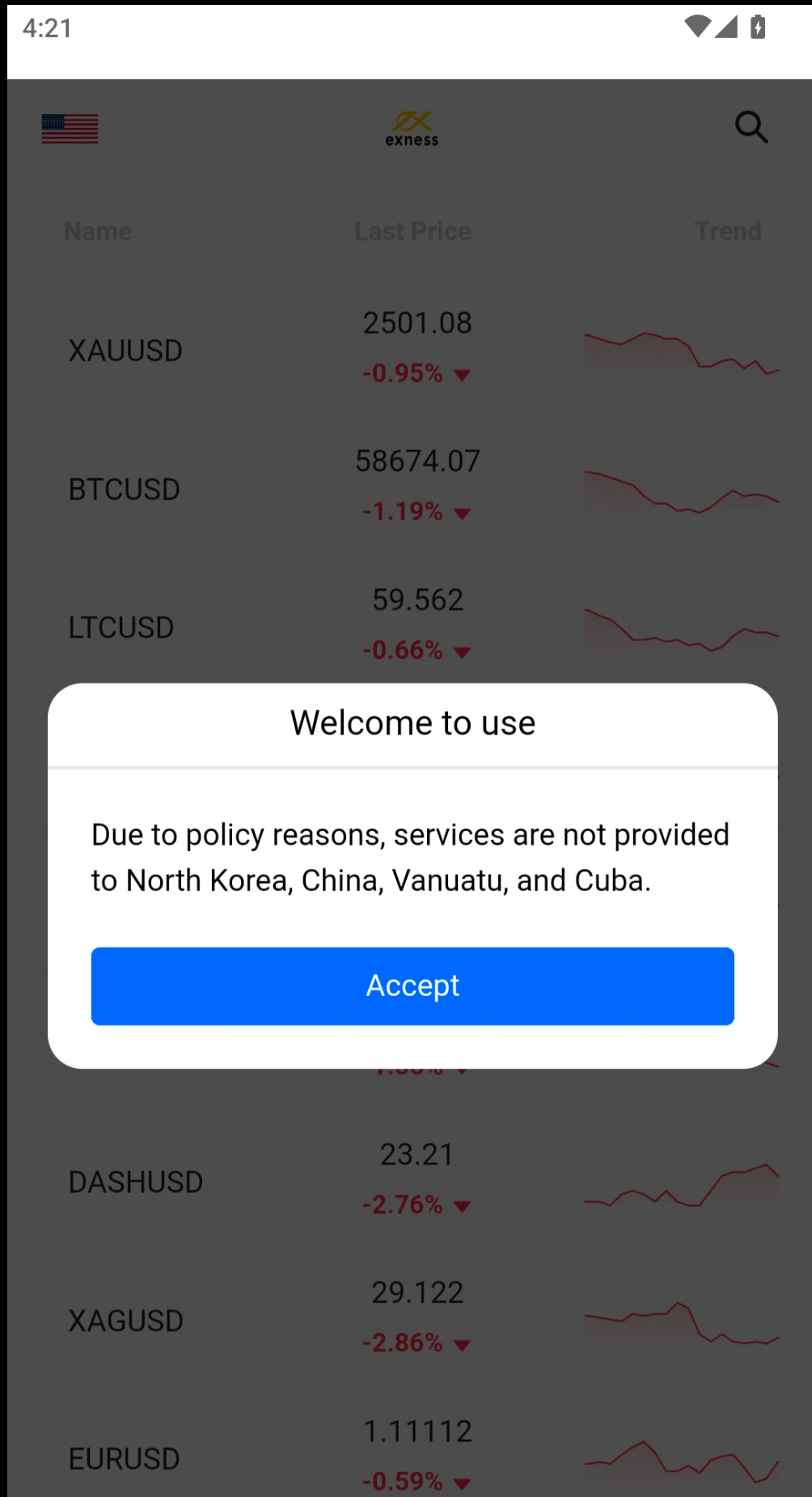

Pig butchering service providers do far more than offer static websites with simple deposit links. As the industry has evolved, they have made efforts to appear more credible and authentic, with offerings now resembling well-known finance applications. Many of the larger platforms claim integration with one of the popular online trading platforms such as MetaTrader. PBaaS providers will often rent a VPS and register as a broker with the trading platform, before leasing access to their customers. Using MetaTrader allows the scammer to display real-time financial information, which helps them appear more credible, but also grants access to a trusted mobile application and recognized brand. See Figure 11.

Figure 11. A credible-looking real-time ticker graph as displayed on the scam websites.

Upon installation, victims are asked to choose a broker (i.e., the scammers) who will then have full access to the funds and the trading tools. MetaQuotes, the Cypriot company developing the MetaTrader platform, rejects all responsibility and claims to be a simple intermediary, leaving the victims to try to track down the individual brokers they interacted with. Figure 12 shows the attribution of a “Meta number” (used for trading) to new victims.

Figure 12. Victim panel displaying their MTAccount number and current balance for each user

Some fraud syndicates can mix real transactions with fictional ones to obfuscate financial streams. With access to valid trading accounts, scammers can move large sums of money, from both legitimate and illegitimate sources.

Mobile Applications

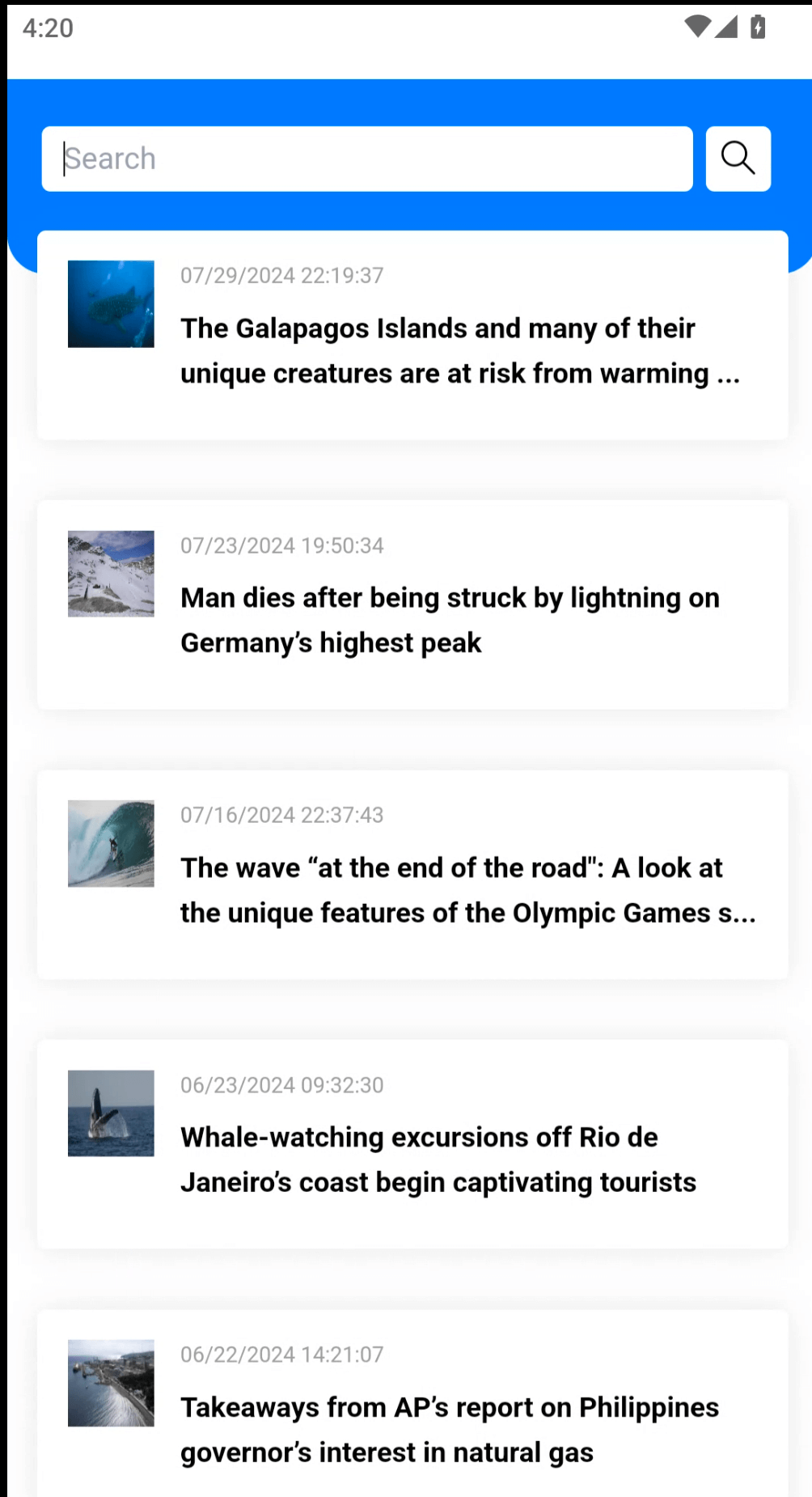

Suppliers of PBaaS have also automated the provision and supply of mobile applications. On Android, this process is simple: users can install any given binary packaged as an .apk. It is more restricted on iOS. Any given iOS developer can enroll a limited number of devices and users into a “testing program,” and there is a thriving shadow economy that provides developer certificates and testing accounts.

Users (victims) receive a .mobileprovision file, and if they approve it from a mobile device, the developer will obtain access to the device’s management suite and be able to install their ‘testing’ binary. This is abused to bypass China’s appstore controls so that users can install gambling, pig butchering and porn apps, and it poses considerable risks to the victims. Apps distributed this way completely sidestep verification programs and can contain any sort of malware. Moreover, devices themselves can then be managed by the developer’s account, offering functionalities such as geolocation, remote wiping or traffic interception.

Some PBaaS actors have chosen to release their apps in real stores, increasing their availability and simplifying installation considerably. To avoid detection by automatic app store code reviews, they have hidden the trading functionality behind decoys. For example, the “news app” in Figure 14 below actually represents a pig butchering panel. The only way to display the trading panel is to enter a specific password in the search bar. Sidestepping the mobile app issue entirely, scammers can also develop a website that looks like a mobile app and asks the user to pin it on their phone’s screen. Although cost-effective, it does not offer the same service quality and usability as a native app.

Figure 13. A decoy news app that is secretly a scam trading platform

Cost Benefit Analysis

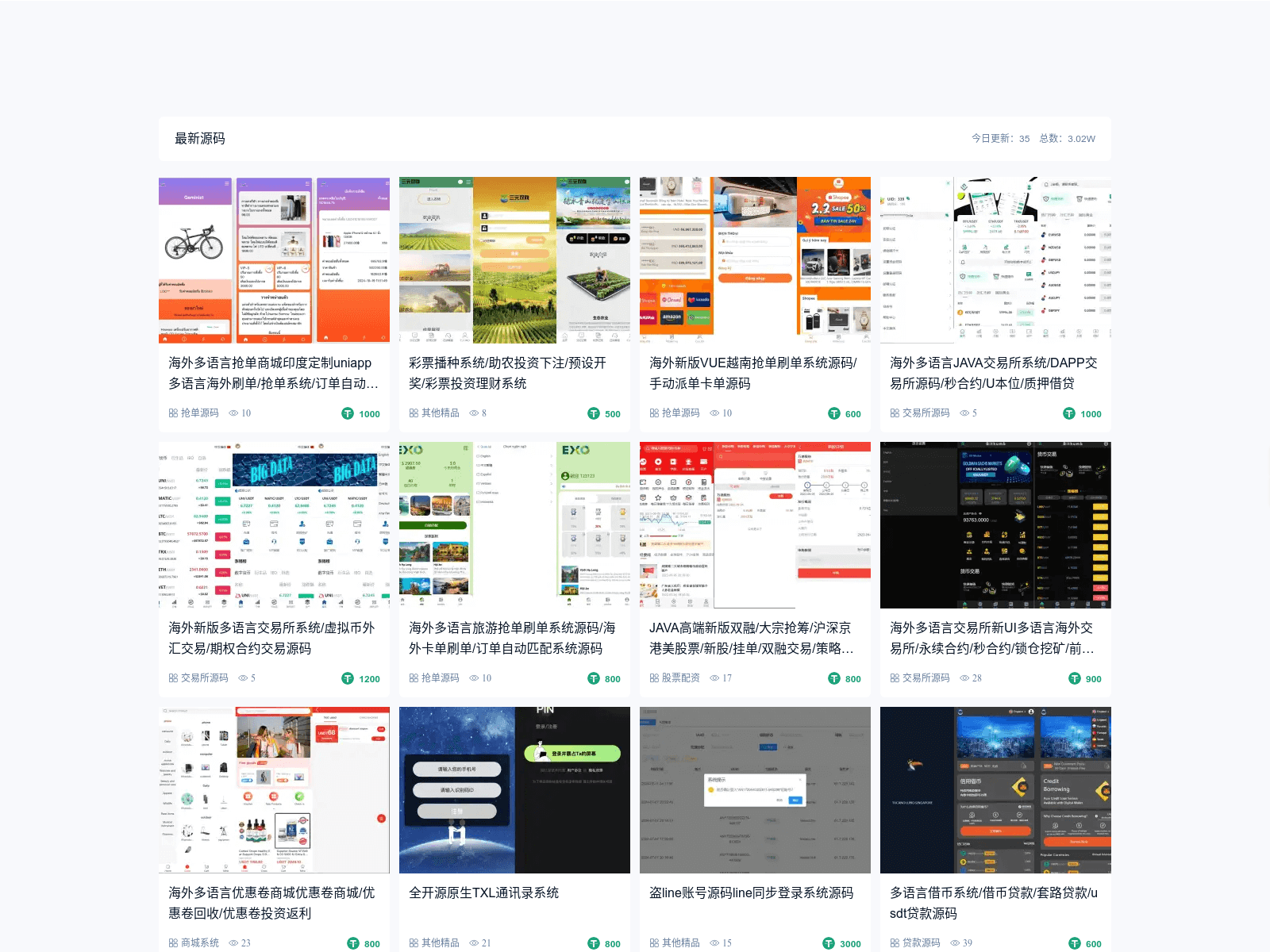

Website templates that include hosting can cost as little as US$50, as shown in Figure 14 below. A complete pack, including a website with admin access, VPS hosting, mobile app, access to a trading platform, company incorporation in a tax haven, and even registration with the relevant local financial regulator, can start at 20,000 yuan (about US$2,500). Through this setup, an operation the size of that in the previously mentioned Jia vs. the United States case, for instance, could achieve a return on investment (ROI) of approximately 70,000%.

Figure 14: Panel of a template seller advertising pig butchering crypto apps and fake shops, another form of cyber-enabled fraud.

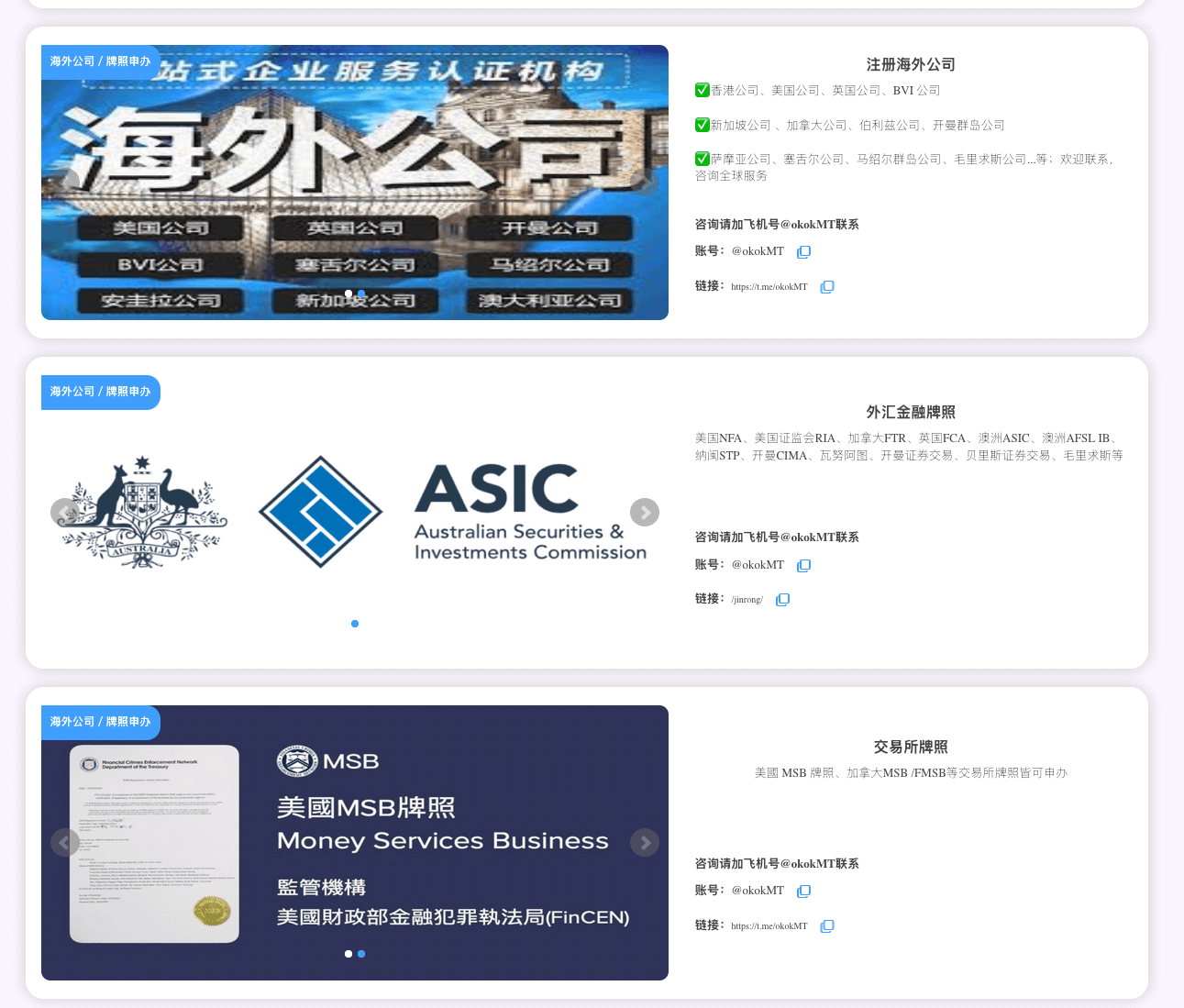

Shell Companies… as a Service?

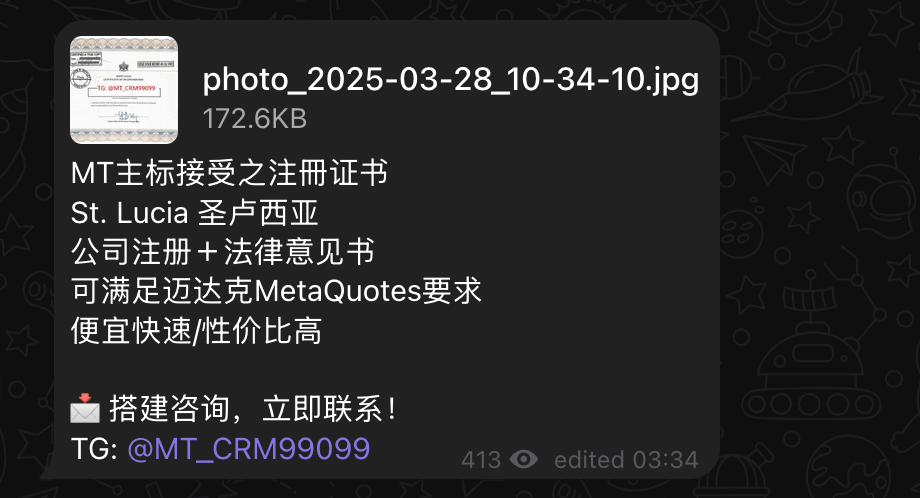

Asian crime syndicates conducting cyber-enabled fraud increasingly rely on professional enablers and facilitators not just for technical infrastructure, but also to help them mask their activities. These facilitators play an integral role in the scam ecosystem, creating ready-made front companies—often registered in bulk—that give scam operations a veneer of legitimacy while helping syndicates obscure complex financial flows across offshore jurisdictions. Telegram marketplaces now openly sell company registrations and nominee directors, particularly in countries such as Cyprus, Malta and the Seychelles, as well as “identity laundering” packages that exploit citizenship-by-investment programs in countries including Cambodia, Dominica, St. Kitts and Nevis, and Vanuatu.

PBaaS actors recognize this and now offer services to create companies for scammers. See Figure 15 for two examples. As we highlighted in our prior pig butchering research focusing on the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, in addition to leveraging PBaaS templates, some UK addresses, even single apartments, have been used to register tens of thousands of such entities with Chinese-linked nominees. We identified specific addresses, often apartments in the UK, where tens of thousands of companies, all with Chinese nominee directors, were registered.

Figure 15. On the left, a template seller advertising incorporation services in Saint Lucia, a Caribbean tax heaven. On the right, another seller advertising some of the companies they created.

Company creation packages often include formal corporate registration with relevant financial authorities. This helps the scammers to establish credibility. See Figure 16.

Figure 16. A template seller offering different decoy websites, as well as company registration and financial licenses.

Conclusion

The explosion of cyber-enabled fraud in Southeast Asia and the billions of dollars in financial losses recorded annually has far-reaching consequences increasingly felt around the world. Sophisticated Asian crime syndicates have created a global shadow economy from their safe havens in Southeast Asia. PBaaS provides the mechanisms to scale an operation with relatively little effort and cost.

Large scam compounds such as the Golden Triangle Economic Zone (GTSEZ) are now using ready-made applications and templates from PBaaS providers. This decentralized service-based business model also makes attribution more difficult, as countless criminal networks can use the same template.

Compounding the situation further, what once required technical expertise, or an outlay for physical infrastructure, can now be purchased as an off-the-shelf service offering everything from stolen identities and front companies to turnkey scam platforms and mobile apps, dramatically lowering the barrier to entry.

Powerful triad networks have pivoted to scamming and cybercrime for a reason: they recognize it is more profitable and far less risky than drug dealing. They know they are safe in their special economic zones, and that international investigations, when they happen, are often too slow to stop them.

As PBaaS continues to mature, scams are anticipated to become more automated, more global, and more adaptive. Countering this ecosystem will require a shift in focus: targeting the service providers, facilitators, financial enablers, and DNS infrastructure that make mass-scale fraud possible.

Footnotes

- See United States District Court for the Central District of California. Case No. 2:25-mj-00355, United States of America v. Zeyue Jia, 01/29/2025.

- Online illegal gambling has moved to a model of ‘whitelabels’, where ready-made casino websites are made available to anybody willing to pay – also called “turnkey”. Baowangs – 包网 – are Chinese speaking groups developing, hosting and running those websites. For more information, you can consult “Vigorish Viper : A Venomous Bet”

- Case 25-mj-00355, United States of America v Zeyue Jia, aka “Jiao Jiao Liu”