On January 2nd, new research revealed that the tremendous growth of the Kimwolf Botnet was fueled by tricking residential proxy services into relaying malicious commands to vulnerable devices on the local Wi-Fi network. Moreover, mobile apps may add devices to a proxy network in ways that may not be obvious to the end user, turning them into an unwitting infection vector. From our DNS telemetry, we found evidence of Kimwolf probing for vulnerable devices using residential proxy services in enterprises and institutions around the world. Alarmingly, nearly 25% of Infoblox Threat Defense Cloud customers made queries to Kimwolf domains, suggesting the presence of proxy endpoints in those networks. This blog contains lessons learned, findings, and recommendations for organizations of all sizes.

I was sitting in a hospital cafeteria while I read Brian Kreb’s article, “The Kimwolf Botnet is Stalking Your Local Network.” The story sent a chill up my back, and I immediately wondered what damage could be done in the hospital setting. New research by Synthient showed how a DNS trick by threat actors, in combination with a lot of vulnerable devices and security holes, allowed the Kimwolf operators to take over millions of devices in home networks in a matter of months. Much of the threat stems from mobile apps with integrated proxy-monetization components and insecure consumer devices, but it feels like the tip of the iceberg. The glue holding all this together is residential proxy services which route internet traffic through consumer devices and internet service providers (ISP), making it appear as though it originates from a residence. While they have legitimate purposes, the security community has seen time and again that residential proxy services can be abused for a range of nefarious purposes.

The article also reminded me of questions I had literally tucked into a note to myself, entitled “weird Aisuru resolutions,” after reading another of Brian’s blogs on the Aisuru botnet. At that time, I scoured Infoblox DNS telemetry to check whether any of our customers had evidence of infections. The Aisuru botnet used DNS TXT records to deliver command-and-control (C2) locations to compromised devices. With a bit of DNS magic, I discovered a few unpublished domains and verified one botnet member using our cloud DNS resolvers… but that “compromised device” was inside a security company and likely a researcher. Either way, the botnet member wasn’t receiving commands because the domains were already blocked by Threat Defense. Aisuru used Google DNS-over-HTTPS (DOH) and so it was possible we didn’t see all the infected devices. In this case, the customer was blocking DOH and redirecting the queries through our cloud resolvers. In any event, we didn’t have much indication of Aisuru in customer networks.

But some pieces didn’t add up. There were a few domains supposedly associated with Aisuru that resolved to non-routable IP addresses, e.g., 127.0.0.1 or 0.0.0.0. We saw these at low levels across multiple customers. These domains didn’t have TXT records and didn’t fit the Aisuru domain profile I had built. Indeed, the one customer with a confirmed Aisuru botnet member didn’t query any of these domains!

It is very time consuming and often super tricky to figure out the origin of a DNS query, especially when we are observing it at a recursive resolver that may be many links away from the origin. The mysterious queries matched the pattern we see for open resolvers and I confirmed a few sources were open resolvers but then drew the faulty conclusion that they were all somehow Aisuru probing open resolvers–a classic example of confirmation bias at work.

I asked around in the security community about the weird resolutions, but finding no answers, I wrote that note to myself and moved on to other research. The revelations from Synthient shed new light on these queries—it seemed that Kimwolf operators were probing our customer networks. Within hours, I was peppering Ben Brundage, the founder of Synthient, with questions. He provided a critical piece of information: an exact timestamp that I could map into our logs.

Kimwolf scans for vulnerable devices through residential proxy services, leveraging existing compromised devices, mobile apps, and other proxy endpoints. Most vulnerable devices are Android TVs, so we don’t expect to see many true botnet members in our Threat Defense Cloud customer environments, which are primarily large enterprises and institutions. That said, the ability to probe the local network and compromise devices is risky enough that organizations should pay attention.

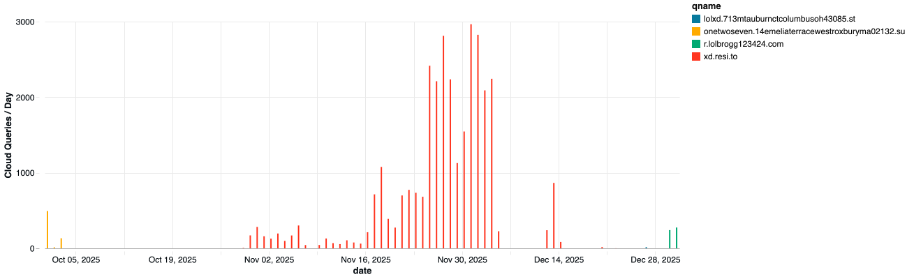

So, what did we see at our DNS resolvers? We had queries from about 5% of our customers between September 2nd and October 3rd for the domain reported by Krebs in November as dominating the global DNS charts. But that was early on, and over time, the number of impacted customers grew substantially. Figure 1 shows the number of queries per day since October 1st.

Figure 1. Presence of Kimwolf botnet queries within Infoblox Threat Defense Cloud customer environments; in many cases, these queries were not resolved due to customer policy settings. On the most active day, 8% of Threat Defense Cloud customers were probed by Kimwolf operators.

The graph shows a gap in Kimwolf queries from early October to early November, which Ben confirmed matches the activity Synthient observed. A new domain, xd.resi[.]to, shows up a few weeks later, also returning non-routable IPs. Only one customer made queries to the short-lived xd.mob[.]to, on November 22nd. Then in late December 2025, we see queries for the newer domains.

In total, nearly 25% of our cloud customers made a query to a Kimwolf domain since October 1st. To be clear, this suggests that nearly 25% of customers had at least one device that was an endpoint in a residential proxy service targeted by Kimwolf operators. Such a device, maybe a phone or a laptop, was essentially co-opted by the threat actor to probe the local network for vulnerable devices. A query means a scan was made, not that new devices were compromised. Lateral movement would fail if there were no vulnerable devices to be found or if the DNS resolution was blocked.

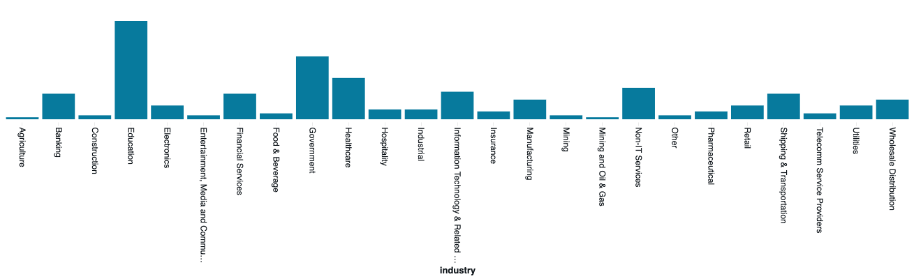

These customers are based all over the world, and in a wide range of verticals, from education to healthcare; see Figure 2.

Figure 2. A distribution of industries with Kimwolf-related DNS queries

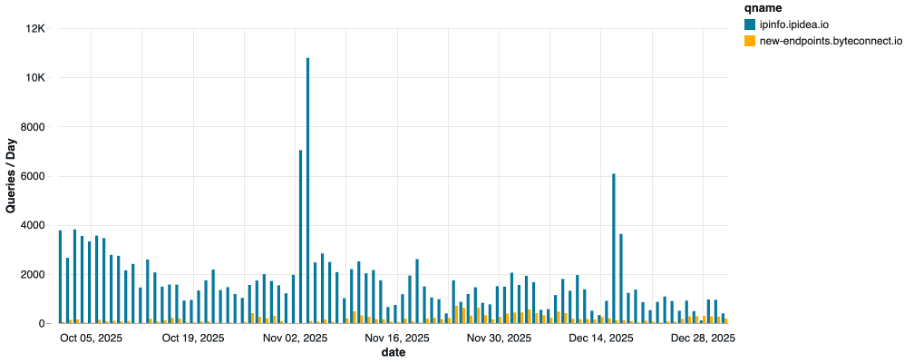

Kimwolf uses and abuses residential proxies to spread and monetize their footprint. Two such companies mentioned in the Synthient report were IPIDEA and Plainproxies. IPIDEA is the largest proxy service in the world, while Plainproxies’ footprint grows through developer adoption of their Byteconnect SDK. In response to Synthient’s vulnerability notification, IPIDEA improved the security of their product, while Plainproxies had not responded at the time of Synthient’s disclosure. Krebs on Security also reported that Plainproxies did not respond to a request for comment.

How present are these two proxy services, independent of Kimwolf activity? Over 20% of Threat Defense Cloud customers made queries to the IPIDEA API endpoint that returns information about an IP address, indicating possible devices with the proxy SDK installed. About a dozen customers made queries to the Plainproxies’ domain that returns a list of proxy relay addresses. Of note, during the time when we saw no queries to Kimwolf domains, we still observed queries for both proxy services (Figure 3). These are only two of many residential proxy services that could be used by threat actors for malicious activity.

Figure 3. Queries from Infoblox Threat Defense Cloud customers to domains related to residential proxy services, IPIDEA and Plainproxies

Like Aisuru, Kimwolf may have very little foothold in Infoblox customer environments. However, the use of DNS and residential proxies to probe networks should be a wake-up call for everyone. This time it is Android TVs, but what if it is heart monitors next time?

Every organization has unique security concerns, but we recommend the following:

- Risk-averse organizations should consider mechanisms, including protective DNS, to detect and block residential proxies within the network.

- Review your DNS query logs, if you have them, for the presence of queries to known Kimwolf domains.

- If you use protective DNS, check your current response policies. Risk-averse organizations should consider blocking bogon resolutions, as well as suspicious and malicious domains.

- Check your IP addresses with Synthient or another organization tracking Kimwolf and residential proxies.

Related Domains:

- xd.mob[.]to (this domain is parked and was used for testing, it seems)

- xd.resi[.]to

- 14emeliaterracewestroxburyma02132[.]su

- 713mtauburnctcolumbusoh43085[.]st

- hahaezretard3.713mtauburnctcolumbusoh43085[.]st

- r.lolbrogg123424[.]com

- ipinfo[.]ipidea[.]io (abused residential proxy service endpoint)

- new-endpoints.byteconnect[.]io (abused residential proxy service endpoint)