Who doesn’t love to eavesdrop onto a juicy conversation? We recently snooped on the communications of an affiliate advertising push notification system whose DNS records were left misconfigured–oops. This mistake allowed us to receive a copy of every ad they sent victims, along with all the metrics they recorded. We analyzed over 57M logs collected over a two-week period that contained advertisements, requests for software upgrades, and other events. It’ll come as no shock to our regular readers that we observed widespread deceptive practices, scam activity, and brand impersonation throughout the data.

As interesting as the data was, the method we employed was even more fun. We used a DNS technique to take control of a domain abandoned by the threat actor by simply claiming it at the DNS provider. For the DNS geeks out there: we took advantage of a lame name server delegation. We warned about this technique last year, which we dubbed Sitting Ducks attacks, in joint research with Eclypsium. As soon as we realized that the actor had neglected one of their DNS records, we immediately called Eclypsium again.

Within an hour, we had claimed the domain at the DNS provider, and our server was flooded with requests from victim devices, sending detailed information about their device and more! This wasn’t an adversary in the middle (AiTM) operation; we had a seat “on the side” of the threat actor’s operations. Every message from the notification server to every victim was also sent to us. See Figure 1.

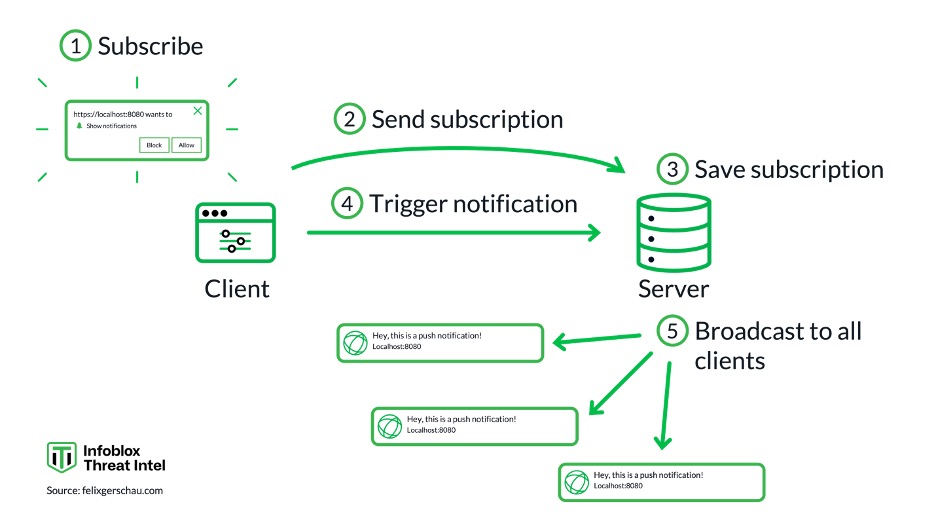

Figure 1. How push notifications work according to https://felixgerschau.com/web-push-notifications-tutorial/

But why listen to just one conversation when you can listen to many? It turns out this actor demonstrated poor DNS hygiene, including multiple misconfigured delegations. Within a day, we’d increased our collection from one domain to nearly 120. Thousands of victim devices were connecting to our server and creating 30MB per second of logs. While we collected traffic for a lot of domains, the actor controlled at least an order of magnitude more. This appears to be a large-scale push-notification advertising operation with a global footprint.

Data analysis showed that while the commercial network might claim to be merely delivering “advertisements” on behalf of their affiliates, based on the observed content, these notifications do not resemble legitimate advertising. Users were bombarded with messages, on average over 140 a day. The titles were in over 60 languages spanning the globe; see samples in Table 1.

| Language | Sample Messages |

|---|---|

| English | “BREAKING NOW 🔥”, “Your number has been chosen!”, “Start winning big!” |

| French | “LE SECRET DE RETAILLEAU RÉVÉLÉ”, “Félicitations!”, “Ne manquez pas cette offre!”, “❌ Votre compte est bloqué!” |

| Spanish | “¡Juega con ventaja!”, “¡Felicidades!”, “Regístrate y recibe!” |

| Portuguese | “Convide 1 e ganhe R$55”, “Hoje é seu dia de sorte!”, “Ganhe bônus agora!”, “BRADESCO: Você possui 42.487” |

| Arabic | “اختيارك إنت”, “مكافأة لاعبين جدد!”, “باقة ترحيبية ضخمة بانتظارك” |

| Russian | “Цензура вместо честности!”, “Поздравляем! Вы выиграли!”, “Баланс: +130 000₽” |

| Polish | “Powiadomienie o wypłacie”, “Masz 2 spiny”, “Rewelacyjna Platforma!” |

| Turkish | “Türkiye’ye Özel Teklif!”, “İnanılmaz Casino Bonusu!” |

| Hebrew | “היתרה שלך: ₪9281 — קבל עכשיו!”, “וירוס בטלפון שלך?” |

| Japanese | “警告:Googleアカウント(1)”, “あなたのアンチウイルスライセンスが間もなく期限切れです!” |

| Korean | “❌ 감염된 파일이 계좌에서 돈을 훔칠 수 있습니다 ❌”, “휴대폰에 바이러스가 있나요?” |

| Vietnamese | “Khuyến mãi lớn cho Trader mới!”, “Đăng ký ngay – Ưu đãi lớn!” |

| Hindi | “आज ही जीतें ₹500 बोनस!”, “आप विजेता हैं” |

| Dutch | “❌ Uw account kan worden GEHACKT” |

| German | “Sparkasse +326,00 Euro” |

Table 1. Sample push notification lures in multiple languages

We collected roughly 60GB of compressed JSON collected over 15 days, and the JSON was extremely rich. It showed the inner workings of this push network at a level never previously published. Whereas we knew from personal experience that the notifications delivered by this network were filled with deception, this data allowed us to verify our experience on a global scale. We found that:

- The notifications thematically use deception, fear, and hope to entice users to click on the link. They include impersonation of legitimate financial services like Bradesco, Sparkasse, Recibiste, MasterCard, Touch ‘n Go, and GCash. Clickbait lures included references to scandals, politicians, and famous personalities.

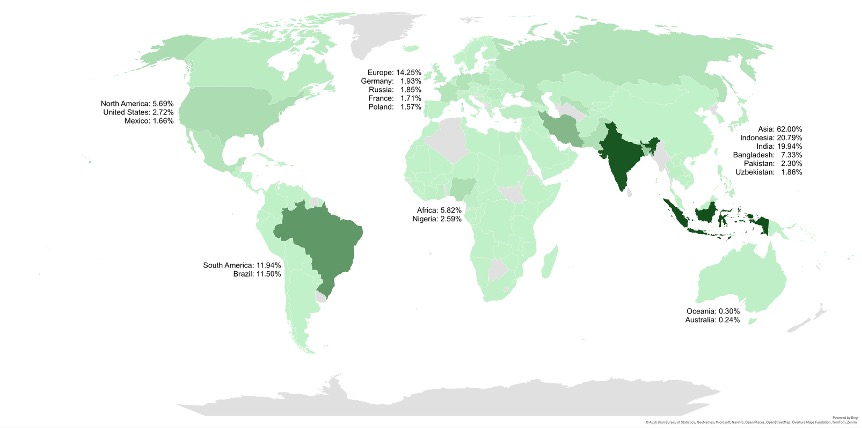

- The domains we gathered served ads to Android Chrome users all over the world, but most of the notifications we saw were sent to Asia, and more specifically to South Asia. Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan represented 50% of all the traffic.

- The median victim would be shown 140 notifications per day, and a total of 7600 notifications over the lifetime of their subscription. Some had been subscribed for over a year to the service.

- The actor encodes a click-through-rate (CTR) estimate in each notification. The highest CTR estimated for any victim at any time is 1 in 175, but the average was 1 in 60,000!

- The data included user clicks, which confirmed these low rates. We saw 630 user clicks in 57 million events.

To the best of our ability, we can estimate that they were making about $350 per day from these ads. Given the total set of domains under their control at the time, perhaps they were making ten times that worldwide. It’s not a ton of money, but perhaps it is enough in their region of the world. After all our analysis, it feels like we know both a lot more and a lot less about the push advertising world.

Our research reveals the underbelly of a push advertising platform engaged in deceptive practices. But it also lays bare the dangers of neglected domains. While we “rescued” the malicious domains, other bad actors are using the same technique to grab dormant domains from legitimate organizations every day. While similar domain-hijacking techniques are used by other threat actors to distribute malware, this research did not observe malware payload delivery originating from the push-notification network described here. One of the most prevalent examples is Vacant Viper: a DNS threat actor who hijacks domains through this very same technique and then uses them for 404TDS, a malicious traffic distribution system known to deliver a variety of malware. If the abandoned domains are still actively used, the attacker can gain access to lots of sensitive information, as well.

Technically, DNS hygiene is the responsibility of the domain owner and many people, including government officials we spoke with last summer who don’t consider exploiting these vulnerabilities as attacks. It’s more like someone dropped their toy on the sidewalk, and someone else picked it up. Whose fault is that? But being a bit on the “goodie two-shoes” side of things, we told the DNS provider what we were doing… just in case.

Note: This research intentionally avoids attributing the observed behavior to any named organization. Similar operational patterns are exhibited by multiple unrelated actors within the push-notification monetization ecosystem. Additionally, all data analyzed in this research was reviewed in aggregate. Personally identifiable information was not retained, and no attempt was made to identify individual users. As an “observer on the side” of the push notification service, we passively received traffic due to a DNS misconfiguration (lame delegation) that caused requests to be sent to infrastructure under our control. We did not access the service’s systems, issue commands, deliver content, or otherwise interfere with the relationship between the service and the user device.

The Back Story

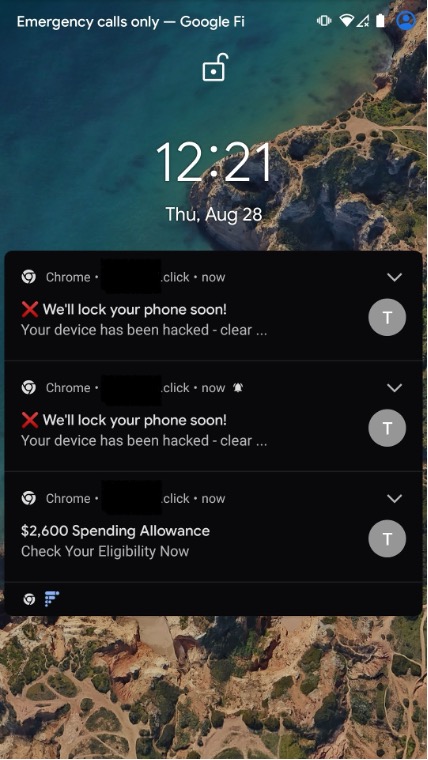

Our adventure began in January 2025 when we knowingly visited a compromised website and clicked “allow” on a prompt that popped up on the screen, subscribing to push notifications from an unknown actor. With one simple click, a custom service worker was downloaded onto our device to manage our “subscription.” The phone began buzzing constantly with an endless series of alerts, often more than 100 a day. The lures ranged from classic scareware to dating to shocking stories of famous people; see Figure 2 for some examples. This is the third blog in our series chronicling these experiences; our earlier blogs include Pushed down the Rabbit Hole and Survey Says: It’s a Scam!.

Figure 2. An example of the false information included in notifications received from this commercial push network.

We suspected that a commercial affiliate advertising network was operating the subscription service but weren’t sure which one. The domain names were randomly generated, registration data protected, and hosting obscured. It was clear, though, that the scale of the operation was large. Hundreds of domains were delivering the same content through the same infrastructure. When a user clicked on one of the notifications, a detailed set of data about the user, the subscription, and the lure were delivered to the push server.

After a few months, things changed. Our device kept receiving notifications, lots of them, but clicking on them led to an error that the domain was unresolvable. At first, we thought the domain resolution was blocked through a DNS server somewhere along the way. After all, we’re not the only ones in the domain blocking business.

Why would we continue to get notifications for an unresolvable domain? It didn’t make a lot of sense until we realized it wasn’t the domain that was the problem: the name servers didn’t recognize the domain. In DNS lingo this situation is called a lame delegation. When a domain is configured at a registrar to use external name servers, but those name servers do not have information about the domain, they are unable to answer DNS queries about it.

In certain cases, someone who hasn’t registered the domain can then go to the DNS provider and simply “claim” it. Once they establish new DNS records, queries for the domain will be answered as directed by the claimant. Tada! Whatever content was sent to the domain, for example email, is now sent to the usurper. They gain complete control, usually for free, all due to a DNS misconfiguration or a forgotten domain.

There are a lot of domains with lame delegation on the internet, so many that we felt “sitting ducks” was the most apt way to describe this vulnerability and attack. Frequently, these sitting ducks are picked up within a few days for use in various malicious campaigns. Sadly, domain owners almost never notice, and the same domain is hijacked repeatedly for use in different attacks.

So here we found ourselves in August 2025 with an affected device that desperately wanted to connect to a lame domain. We felt compelled to rescue it. We were expecting to see connections from affected devices but were surprised by the torrent of data we received.

Push Notification Services

Push notification services were designed so that applications, such as browsers, could deliver content to users under a subscription model, providing users with up-to-date information without having to visit the site or open the application. It’s also a model frequently abused by threat actors to obtain a form of persistence on the user’s device.

For this story, we only need to know a few things: the protocols involved and the implementations. To learn more, see this article and this article.

To establish a subscription service on a user’s device, the website needs to do the following:

- Gain permission from the user to send notifications. While this is intended to be a clear choice to the user, many threat actors use deception to get permission. The prevalence of captchas, cookie warnings and other pop-ups have conditioned most of us to just click accept without reading anything. Actors use this to their advantage, disguising subscribing to notifications as just another thing you need to click through to actually get through to the website you are visiting.

- Establish the subscription with the application’s push notification service, which manages the actual delivery of data to the client. While the third-party service, e.g., Google’s Firebase, technically delivers the messages, they are encrypted and not visible to the push service.

- Place a service worker on the device that handles incoming messages, manages software updates, and deals with data analytics. The service worker will be automatically updated during the life of the subscription.

When the user clicks on a browser notification, it will follow an embedded link, which may not include the original subscription domain. For example, if the user agreed to receive alerts from domain A, when clicking on one of the lures, they may instead be sent to, or quickly redirected to, domain B. This misdirection is what we showed earlier in Figure 1.

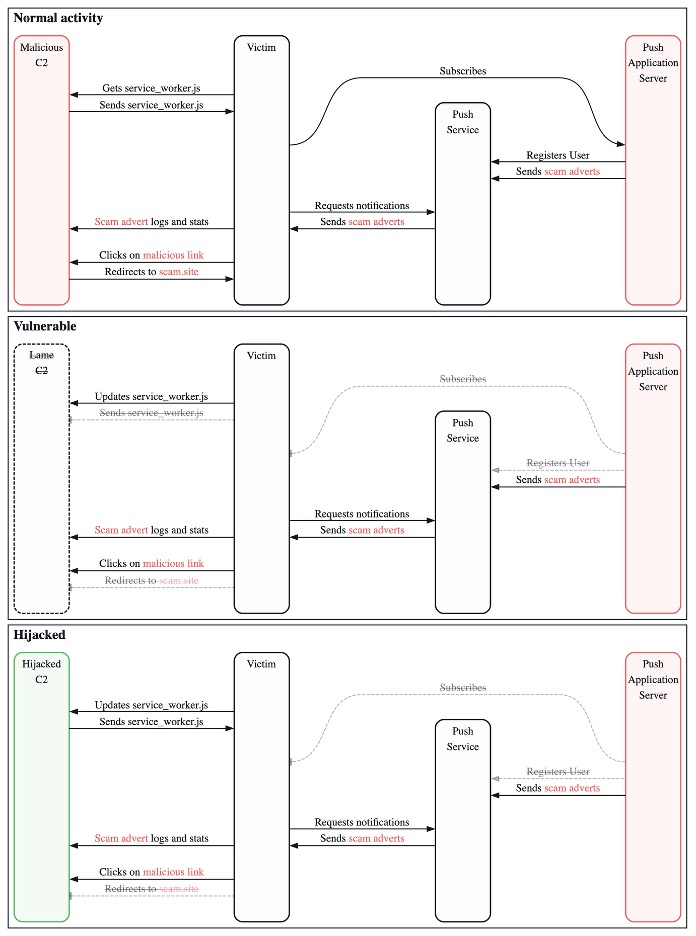

In our case, the lame domain was used to host the service worker software and to redirect victims to scam offerings when they clicked on a notification. The notification URLs contained an automatic redirect to a fixed domain that funneled traffic into a traffic distribution system (TDS) run by the affiliate advertising network. The data we collected was a combination of requests for software updates, advertising details from the service worker, and individual user clicks on notifications. Figure 3 shows a comparison between the original push notification configuration and after we freed the domains.

Figure 3. A comparison between normal traffic flow for the push network (the state where it was vulnerable to a Sitting Ducks domain takeover) and the state where messages are copied to the hijacker

Data Analysis

When we first took over these domains, we were unsure why they had been abandoned. After all, even with those domains being left lame, victims still receive malicious push notifications, they just can’t reach the advertisement. It doesn’t seem like it would be much effort for this actor to keep the operations going.

Given that the goal of advertising is to make money, and dropping the domains meant lost opportunity to make money, we strongly suspected that they didn’t mean to abandon their domains. After all, if large organizations are vulnerable to sitting duck attacks, it seems likely that a threat actor whose primary business is not cybersecurity could also carelessly leave their infrastructure vulnerable.

Actor Capabilities

To our surprise, all the tracking, all the notifications, and all the logs our new domains were receiving were in clear text. The actor did not bother to encrypt anything; the most difficult deciphering we had to do was decode a few Base64 strings.

And that is not for a lack of things to hide! One of the main features they use to personalize ads for each victim was a simple list of keywords, which are typically used to target specific audiences. Like other affiliate advertising networks, this one offers several verticals including dating, nutra, sweepstakes, and gambling. Each time the push network sends a notification to a victim, it also includes all the information used to track victims. Each notification log contains the keywords associated with that user as one of the many parameters of a JSON object.

We knew that a lot of the scams being advertised were linked to fake security breaches, so we assumed we would find keywords like “virus” or “malware,” but no… as far as we could tell, they used the keyword “news” to mean anything but adult content. Every other keyword they used was sexual. We’ll spare you the ones we unfortunately had to look up, but some of the more generic keywords included: adult, bisexual, dating, extreme, feet, gay, and VR.

This threat actor also tracks a litany of things that, we assumed, would help them distribute highly targeted ads. The platform boasts about their advanced targeting, which they claim will help advertising affiliates customize incoming traffic for a high return on investment (ROI).

When they first subscribe, the victim’s device sends its information to the notification server. This data is then sent back to the victim in clear text as part of each notification they receive! Meaning that we could see this information for all the victims who sent a request to the domains we had rescued. This includes information about their OS, their phone model, their internet service provider (ISP), and the date when they first subscribed to these scam notifications.

Each victim is assigned an SID, which we assume stands for “subscriber ID.” The threat actor tracks victims’ behaviors, whether they close, ignore, or interact with the scam notification they have just been shown. Each victim also regularly sends requests to the actor’s C2 to make sure they keep an up-to-date record of their victims’ IPs

It’s said there is no honor among thieves, and there may be less among affiliate advertisers. As a result, everyone involved in the industry has some kind of fraud protection in place. The actor knows that people will try to abuse their system, so they implement various features that let them separate real victims from anyone else who is a bit too curious. The platform offers a feature that identifies IP mismatches: if a victim responds from an IP that does not match their record; an “IP mismatch” flag is set. They also look for User Agent string mismatches, geo location mismatches, ISP mismatches, and they track victims who click on notifications after their TTL is meant to have expired. For some reason, these fraud prevention features are not always activated, so they might charge advertisers extra to make sure their “ads” are shown to real people.

The final kind of metadata we could see from each notification that the victims logged was data tracking the actor’s operations. They track information about each ad: the ad’s “publisher,” the ad’s payment model, its cost, its estimated click through rate, the domain where the ad came from, and basically everything they need to track their revenue, the total number of notifications they have sent to each victim over the life of their subscription, as well as how many ads they had been shown that day. They also track information like the language of the ad, and the geolocation of their victim (Figure 4). All of this gave us great insight into their operations.

Figure 4. Map showing the percentage of notifications pushed to victims in each country

From looking at the location of all the victims, two things were clear to us: this threat actor has the ability to deliver scams or other malicious content to basically anyone on earth. Despite this, most of the notifications we saw were sent to Asia, and more specifically, to South Asia: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan represented 50% of all the traffic we were seeing.

The Victims

As we noticed that most of the victims were from countries where advertising rates are low, a thought started crossing our mind: maybe those malicious notification servers were abandoned because they were not profitable? This isn’t foreshadowing or anything…

TDSs and advertising threat actors are always trying to hide their most malicious activity from prying eyes, and there is only so much we can do to go around their evasion techniques. So, receiving logs of real malvertising traffic was a great opportunity for us to see what real victims are experiencing, and we were not disappointed.

We initially thought that victims were being sent many fewer ads than we were but quickly realized that we were wrong. It turns out that the actor’s platform sent notifications to victims in batches of up to 20. Each notification had a delay parameter, which meant victims would get notifications at regular intervals throughout the day.

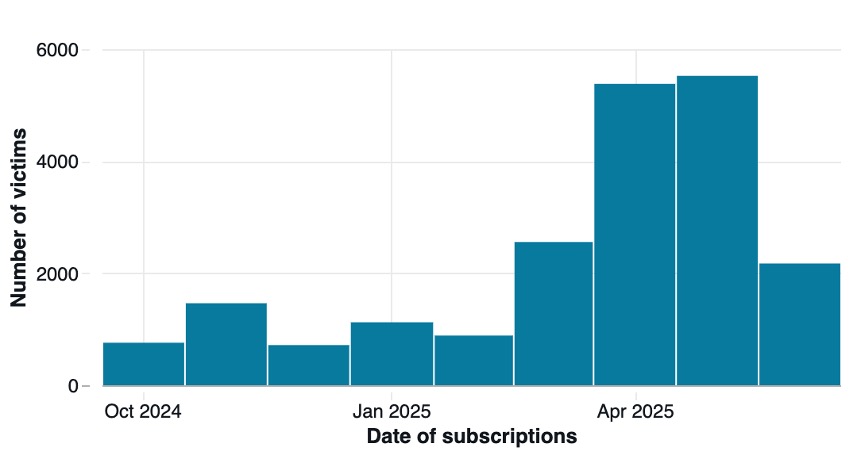

The median victim would be shown 140 notifications per day, adding up to a total of 7600 notifications over the lifetime of their subscription, which roughly lined up with the number of notifications our threat research phone was getting. We also examined how long the scam victims would stay subscribed to the notifications. These scams are extremely obnoxious, and would make using your phone a minefield, where you could accidentally click on notifications that happen to pop up at the wrong time. Surely most victims would unsubscribe from these notifications as soon as they could. But as the graph in Figure 5 shows, based on the data as of October 2025, a non-negligible number of victims had been subscribed to these notifications for up to a year!

Figure 5. Number of new victims per month from October 2024 through June 2025

We suspect these malicious ads aren’t really trying to get you to pay attention to them… they might be just try to trick you into clicking. And that kind of explains why they send hundreds of ads a day to all of their victims: The goal isn’t to target ads to the people who will be the more likely to engage with them; the goal is to try to trick people, to inflate the numbers, and make it look like traffic on the advertiser’s website is increasing. With so many notifications, it is easy to accidentally click one.

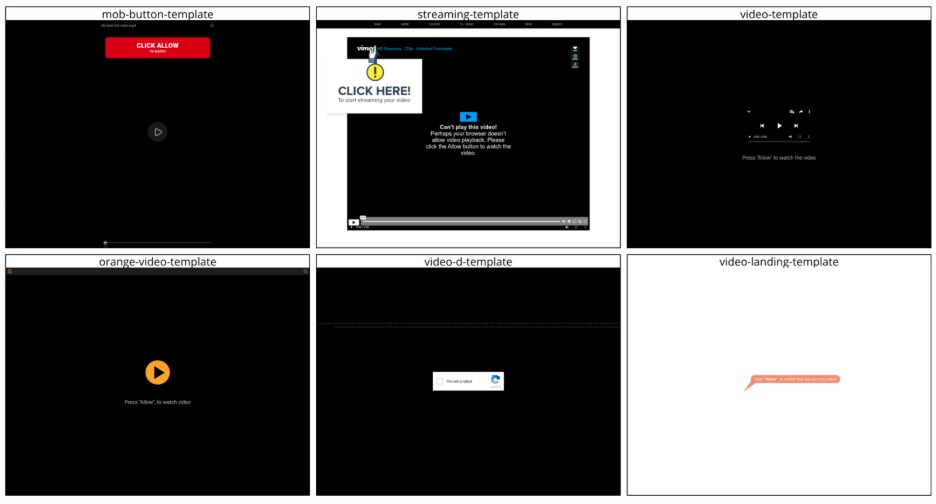

What actually happens when victims click on these notifications? We know that when threat researchers click on them, we often get shown decoy pages, but sometimes we do get redirected to really bad (easy to spot) scams through TDSs. Is that actually representative of victims’ experiences? Well, it turns out that the metadata contained in each notification lets us know what victims are going to be shown if they click! It doesn’t indicate what domain name someone will be sent to, but it does specify which template will be shown to the victim. Notifications can lead to a few different kinds of templates. Some have very generic names, like “video-template” or “loading-template;” some seem related to security, like “secure-template” and “captcha-template.” Most remind us that this threat actor specializes in adult content, with “dating-template,” “twogirls-template,” “wanna-fuck-template,” and many others (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Screenshots of the landing pages of a few “safe for work” templates

The data showed that every ad sent to the victim requested push notification subscriptions for new sites. This is done because browsers require users to occasionally confirm they want to be subscribed to push notifications. If users fail to do so, their browsers will eventually block these notifications. This may explain why we were still receiving requests to subscribe to notifications from the server we took over despite it being abandoned for days.

One thing that was making us realize how few people were actually clicking on those ads was that this threat actor seems to be estimating the Click Through Rate (CTR) each ad might get, but their estimations are pathetically low. Which is confusing because it is a number that they are providing, both to advertisers and victims!?

According to the actor, their highest CTR estimated for any victim at any time is 1 in 175, which wouldn’t be too bad, but the average was 1 in 60,000! It gets even worse when looking at their median CTR: over half the subscribers click once for every 950,000 impressions!

We thought that there must have been something wrong with their estimation process, so we computed the effective CTR we observed over the 15 days of logs we had, and it turns out that they were surprisingly not far off, with an effective CTR of 1 in 80,000, equivalent to a grand total of 630 clicks out of the 52 million ads we logged.

The Notifications

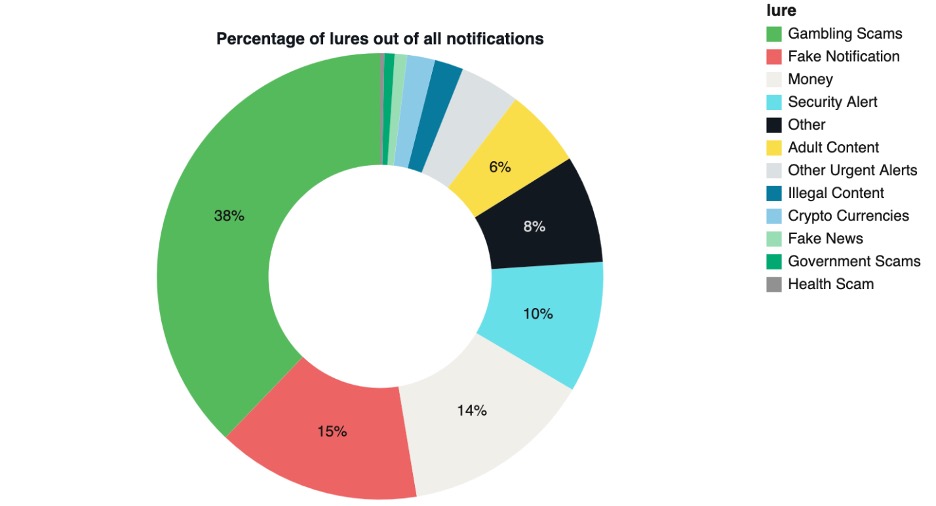

The notifications used deception, fear, and hope to entice users to click on the links. The themes included impersonation of legitimate financial services like Bradesco, Sparkasse, Recibiste, MasterCard, Touch ‘n Go, and GCash. Clickbait lures included references to scandals, politicians, and famous personalities. The use of figures like Elon Musk led to investment scams and fake news sites. Other notifications led to adult content scam sites, in which victims likely unwittingly interact with AI bots and paid personalities, while giving rights to their personal text and images to the website for commercial use. Scare tactics typically led to unnecessary anti-virus subscriptions. While the affiliate advertising ecosystem is structured in a way that distributes responsibility across multiple services, the behavior of associated partners and affiliates remains relevant when assessing ecosystem risk. Figure 7 shows a distribution of lure types we observed.

Figure 7. Percentages of the different types of lures used in the notifications we analyzed

Their Economy

One question remained: The domains we took over had been running for a while, so how much money did this threat actor actually make with this push notification infrastructure? Considering how few people actually click on the notifications, were the campaigns even profitable? If not, that might explain why they abandoned their domains.

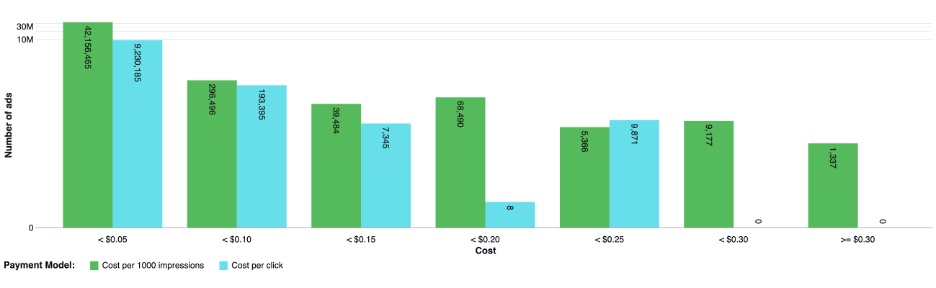

This notification network has two different cost models: Cost Per Mile (1000 impression / CPM), and Cost Per Click (CPC). Considering how low the click through rate was, we assumed that ads using the CPC cost model would make them a negligible amount of money, and after verifications, we were right. Over the 15 days of data we looked at, ads using this cost model generated $1.80 (that is correct–the dot is not misplaced: one dollar and 80 cents).

So, we focused on the cost of the CPM ads. To the best of our ability, we can estimate that they were making about $350.00 per day from these ads. Not to minimize the value of the dollar, but this seemed very low.

The ad publishers here are all sketchy, so we are not really rooting for them, but we can’t help but wonder what they get from advertising on these platforms? One thing that confused us from our logs at the start of our analysis was that the same victim would be shown the same ad multiple times. We started doubting the integrity of our data, and tried to remove duplicate entries, but there were basically none! There were partial duplicates for sure: the same ad being pushed to the same victim at the exact same time with the exact same notification body and title. Each time, the price of the notification would be slightly different, so we were a bit perplexed… until we realized that each time, these duplicated ads had different delays.

Different delays mean that despite getting paid per 1000 ad impressions, this threat actor shows victims the same ad, up to 20 times per day. Obviously, this is annoying for the victims who get spammed with the same scam more than once, but this must also be a genuinely bad investment for the “advertisers” trying to scam victims, right? The likelihood that someone who did not fall for your scam on the 19th time that day falls for it on the 20th time must be incredibly low. This threat actor isn’t just scamming regular people; their pricing and delivery practices appear to disadvantage their own advertising affiliates—which is consistent with public complaints about the platform.

At this point, something seemed off, so we tried to figure out what was impacting the price of ads, and what we might be missing.

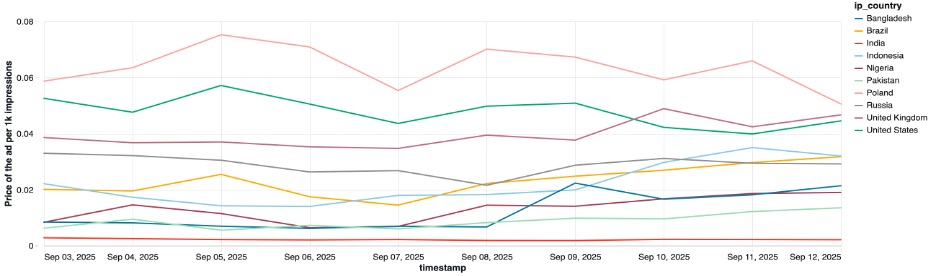

We looked at the parameters that influence the price of ads for other similarly shady push notification services we are tracking (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Price of notifications per day per target country

As expected, victims in some countries are more expensive than victims in other countries. Importantly, victims in India are worth basically nothing, and as we mentioned before, about 20% of the notifications we tracked were sent to victims in India. The other interesting aspect of this graph is that, regardless of the country to which the ad is being pushed, the average CPM (Cost per 1000 impressions) is still very low. From looking at publicly advertised pricing and features commonly promoted by similar push-notification monetization services, we would normally expect prices significantly higher than those observed in our data. It is unclear whether the discrepancy reflects differences between publicly advertised pricing for comparable services and the subset of traffic we observed, or whether it is specific to the domains included in our dataset.

As shown in Figure 9 below, most ads cost less than 5 cents (note the graph uses a logarithmic scale) regardless of the payment model used. One important thing to note is that the number of ads per price bracket doesn’t decrease either logarithmically or linearly. For CPM ads, there is a sort of plateau as they start costing more than 25 cents. For CPC ads, their number oddly vanished around under 20 cents, but a surprisingly high number of them cost between 20 and 25 cents, which seems to be their maximum cost. We can only really speculate as to why that is, but one guess is that there is some kind of increased competition for more valuable victims, driving the price of ads targeting valuable users higher than expected.

Figure 9. Number of ads observed per price bracket

Apart from the country their victims are from, it is unclear if any of the other “features” this threat actor offers to their publishers are valuable. For example, they have an “HQ” feature (presumably standing for “high quality”), but the victims with that flag are not being pushed more expensive ads than anyone else. Their IP mismatch feature also doesn’t seem to work, so the flag is often set to True despite the victim using the same IP as when they were sent ads. And with regards to their other FP prevention features, we could not verify any of them were reliable, as none of them ever triggered. Even if those features were working as intended, it seems like either: “advertisers” do not trust them, as they have no impact on the bidding price for ads; or they do not care about who they advertise to, potentially because they have no other option to advertise their scams, and they have accepted that victims accidentally clicking their ads is the only way they can get traffic.

The last factor we thought might influence the price of ads was their content. We classified ads according to their lure, trying to find out whether some ads were inherently more valuable. As Table 2 below shows, this does not appear to be the case. No matter the kind of ads, and the lure they use to deceive victims, they are all priced roughly the same.

| Notification Lure | Notification Count | Victim Count | Average CPM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gambling Scams | 19,674,313 | 19,635 | $0.01 |

| Money | 7,227,396 | 18,415 | $0.01 |

| Other | 4,071,338 | 16,923 | $0.01 |

| Fake Notification | 7,695,239 | 16,180 | $0.01 |

| Adult Content | 2,981,009 | 15,884 | $0.02 |

| Security Alert | 4,948,413 | 15,505 | $0.02 |

| Other Urgent Alerts | 2,262,384 | 15,420 | $0.02 |

| Crypto Currencies | 1,051,895 | 9,464 | $0.02 |

| Prohibited Content | 1,087,706 | 9,336 | $0.01 |

| Fake News | 463,588 | 7,706 | $0.02 |

| Government Scams | 389,605 | 6,518 | $0.02 |

| Health Scam | 152,825 | 2,170 | $0.01 |

Table 2. Number of notifications, victims, and the average CPM per lure category. (Note that victims can be counted more than once in this table if they have been pushed notifications with different lures.)

No matter what variable we tried to isolate, how much we tried to clean up our data to remove outliers and make sure we were not comparing apples to oranges, we couldn’t find anything to explain the low price of those scam push notifications. One possible explanation is that the infrastructure was no longer economically viable.

Distributed Deniability

The operational characteristics observed in this push-notification monetization service align with patterns commonly seen across similar services in the gray-market advertising ecosystem. These patterns include the use of Telegram-based channels for affiliate recruitment and promotion, including Russian-language channels, as well as infrastructure and business models frequently associated with Eastern European push-monetization operations. Discussions on underground advertising forums regularly include complaints and allegations of deceptive practices directed at services exhibiting these characteristics. Together, these factors illustrate how responsibility and accountability are often diffused across interconnected services within this ecosystem.

In this service, the notification hyperlinks contain a rich set of unencrypted data. Every user click sends detailed information to their server that records the bidding process, images used in the notification, and data about the device. The message is assembled from components spread across commercial content distribution networks (CDNs) that market their services to gray-hat and black-hat advertising operations. Images are hosted on one service; user information is tracked on another. See Figure 10 for some of the component images in notifications from this service which are loaded from different providers.

Figure 10. Individual images shown in browser notifications are fetched from dedicated servers run by separate commercial entities

Ultimately, the network is dependent on the services of a variety of other commercial entities to operate. Some of these are abused; their customer base includes both legitimate and sketchy actors. But others are consistently associated with infrastructure used in cybercriminal activity, whether by choice or circumstance. These providers, whether they be hosting providers or software services, make scam and malware distribution at scale possible. At the same time, each one is typically only one component of a very complicated operation. Regardless of where these commercial entities are registered, we believe the micro-segmentation of services that make this all possible is a structure that results in distributed operational responsibility.

Beyond the distributed nature of the affiliate advertising economy, many scammers view different types of fraud with relative morality. For instance, investment scams might be viewed as pure theft. But they perceive other types of digital fraud as lesser evils when the user agrees to terms and conditions (T&C). Of course, most users do not review these documents, and if they do, they are unlikely to understand the tangle of legalese, but scammers believe they are absolved of any wrongdoing by the “fine print.”

We’ve noticed that many push monetization services have adopted language that warns the subscriber that “notifications may contain errors, inaccuracies, or content that you find objectionable.” They, the transmitter of this information, accept no blame. They also sometimes include directions on how to change notification settings in the browser, even though users are unlikely to see these warnings. See Figure 11.

Figure 11. These screenshots show partially extracted terms and conditions from a commercial push monetization service. This service is not the subject of this paper and is shown solely as an illustrative example.

Advertising networks often have guidelines for the “creatives” that are used in notifications. These requirements often walk a thin line between deception and outright lies. They might claim to reject messages like “Your computer has HDD malfunction” but allow “Your computer might be damaged” because it is “less aggressive.” We have studied several commercial affiliate advertising networks and have yet to find one that enforces their published guidelines.

According to the website of the platform that we analyzed, their compliance team reviews all advertising content and will purportedly reject deceptive messages. But the data included notifications like:

- “¡Android infectado con MALWARE!” (Android infected with malware!)

- “System benötigt einen Scan” (System needs a scan)

- “bellek dolu” (memory full)

- “5 viruses detected!”

- “WhatsApp račun je blokiran” (WhatsApp account blocked)

- “Sparkasse: Zahlungseingang” (Sparkasse Payment Received)

From millions of push notifications, we saw these lures are the rule, not the exception. Until push notification networks distributing deceptive content place firmer controls on their affiliate content, we consider them a high risk. Fine print that puts the burden of fraud onto the victim is not sufficient.