When most people say DNS, they are thinking about the global DNS system, the official mechanism for resolving domain names on the internet. But shadow systems exist. Visiting a website relies on a DNS resolution chain that iteratively queries authoritative name servers within the distributed DNS hierarchy to get an IP address. This resolution all happens in the background, and users put a lot of trust into DNS resolvers without even realizing they exist. If the IP address of those resolvers is changed, a website’s domain name might resolve to an entirely different IP address, sending an unwitting visitor to an entirely different location.

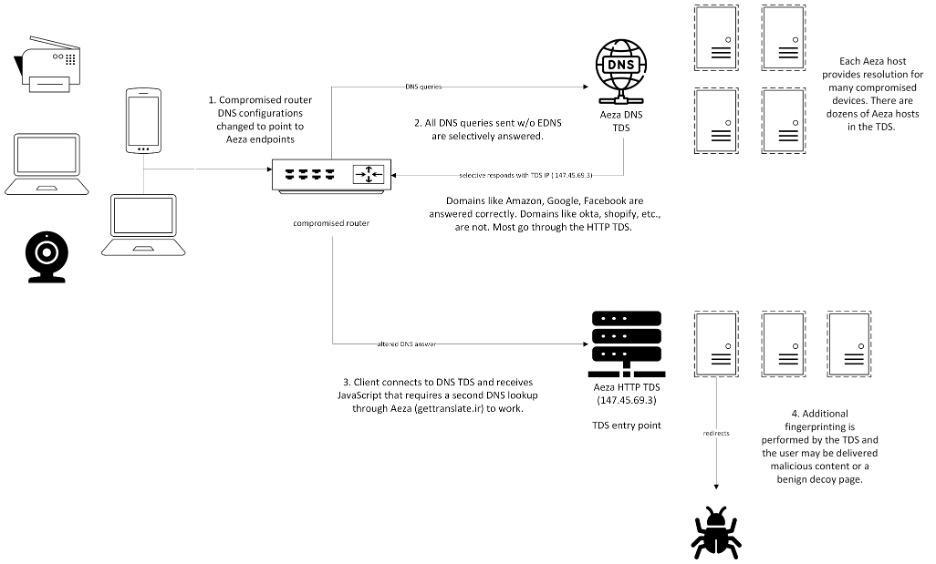

We discovered compromised routers whose DNS settings had been changed to use shadow resolvers hosted in Aeza International (AS210644), a bulletproof hosting company (BPH) sanctioned by the U.S. Government in July 2025. The DNS change meant that every device behind that router was serviced not by the local ISP’s DNS resolvers, but by the threat actor. The Aeza resolvers selectively altered the responses, allowing them to direct users to a range of malicious content, all through a DNS resolution. This shadow network also incorporates an HTTP-based traffic distribution system (TDS), further allowing the actor to fingerprint users and funnel them to content of the actor’s choosing. The combination of an alternate DNS and TDS, along with a clever DNS trick to prevent probing by security groups, has allowed the actor to remain undetected for years. Figure 1 provides a high-level overview of how the system works.

Figure 1. An overview of the two-part TDS hosted in Aeza International

This system appears to be operated by a financially motivated actor in the affiliate marketing space. Since mid-2022, they have directed user traffic to adtech platforms through “smartlinks,” a mechanism used in affiliate advertising to fingerprint a device and redirect the user to “advertising” content. The links contain unregistered domains and require interaction with one of the shadow DNS servers to resolve. We use quotes here for advertising because often this content is malware or scams.

While the actor’s verified activity is affiliate marketing, they could have interfered in other ways with devices in the network. As a trusted source, they could alter DNS records for any domain and run adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) operations, not just for websites, but for the domain names of critical applications and services.

We cannot emphasize this enough: the DNS resolver is in a position of power.

Shadow DNS Network

The threat actor compromises routers, particularly older models, and changes the DNS settings on them. Every device using that router will unwittingly use the shadow DNS network.

One user described their experience in early 2025 in a Reddit post titled “HELP im going insane” [sic]. In a now-deleted response, another user describes their own experience, which hints that the exploitation goes beyond the router exploitation that we verified; see Figure 2. This threat is deceiving and will lead to the assumption that a problem exists in other services: online users complained that they could not access Google Sheets or that they were regularly redirected when using Google Chrome. These user reports indicate that the threat actor has manipulated DNS in some cases where we would expect the encrypted DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) to be used and the router-set DNS server to be ignored. It’s possible that in these cases, the user has turned off the secure DNS option or there is another underlying compromise on the device; we don’t know.

This happened to me - I use OpenMTCPRouter (virtual router instead of a physical one, based on OpenWrT), with a public (virtual private server) VPS for aggregating network connections, I had misconfigured network rules, which exposed my "router" virtual machine to the internet, which was exposed publicly via my public VPS, which when compromised, had several things done: - did DNS redirection to https://gettranslate[.]ir:18443 and profitablecpmrate.com. - Locked out the root/admin user - Loaded a crypto miner

Figure 2. A Reddit response to a user post about being unable to use their home network without interference; this response and the original question are now deleted but were online in November 2025.

There are dozens of recursive resolvers in the shadow Aeza network. Each compromised router is assigned a pair of them for DNS resolution. Answers to queries contain a time-to-live (TTL) of 20 seconds, forcing the devices to regularly connect to the Aeza resolver and ensuring that malicious redirects are difficult to replicate.

The threat actor modifies responses based on the domain name requested, the router’s location, time between queries from the router, and randomization. Extremely popular domains such as Google or Facebook are, in our experience, usually answered truthfully. Others that are still popular or related to critical services may be modified. For example, we have seen altered responses for domains like shopify[.]com and okta[.]com. The resolvers will also answer queries for non-existent domains, which are often seen because of typos or as leaks from devices on a network for local domains.

Answers from the resolvers change based on several factors, and the correct IP address is frequently returned so that malicious redirects are limited and unpredictable. If any of the resolvers are queried “too often” in a short period of time, they will return 255.255.255.255 to the query. The reason for this response in lieu of the correct resolution is unclear to us.

The DNS portion of the TDS uses a surprising trick to hide from security testing: it only answers DNS queries with a specific format. For example, if you query one of the name servers, e.g., 89.208.105.113, for the IP address of shopify[.]com, under most conditions you will get an error:

;; Warning: Message parser reports malformed message packet.

This stumped us for months. We knew that the queries were resolving for some devices but couldn’t trigger a response ourselves. Persistent tinkering led to a solution! If we sent a query without the Extension Mechanisms for DNS (EDNS0) included, voila! The name server replied.

This restriction by the threat actor is surprising because EDNS0 was introduced over a decade ago and is part of a standard DNS implementation. As a protocol extension, EDNS0 can serve a variety of purposes, including increasing the accepted size of a response, supporting DNSSEC, and providing hints about the client device location. Because most DNS resolvers enable EDNS0, queries to the Aeza hosts will usually result in a malformed response.

Here is how to trigger a response from the command line:

dig +noedns @89.208.105.113 shopify.com

After building signatures, we found over three dozen resolvers for the system in early November 2025. Some of those IP addresses include: 104[.]238[.]29[.]136, 138[.]124[.]101[.]153, 193[.]233[.]232[.]229, 45[.]80[.]228[.]233, 89[.]208[.]103[.]145.

Thus far, we have only triggered a response by disabling EDNS0, but we suspect there is more to be learned. The number of routers that don’t use EDNS0 is dwindling and would seem to limit their operation. Additionally, from one of our research partners, we know that the threat actor is broadly and regularly searching for new routers to attack. So, why keep this restriction? But….

Getting the DNS resolvers to respond is only the first piece of this puzzle….

The HTTP TDS

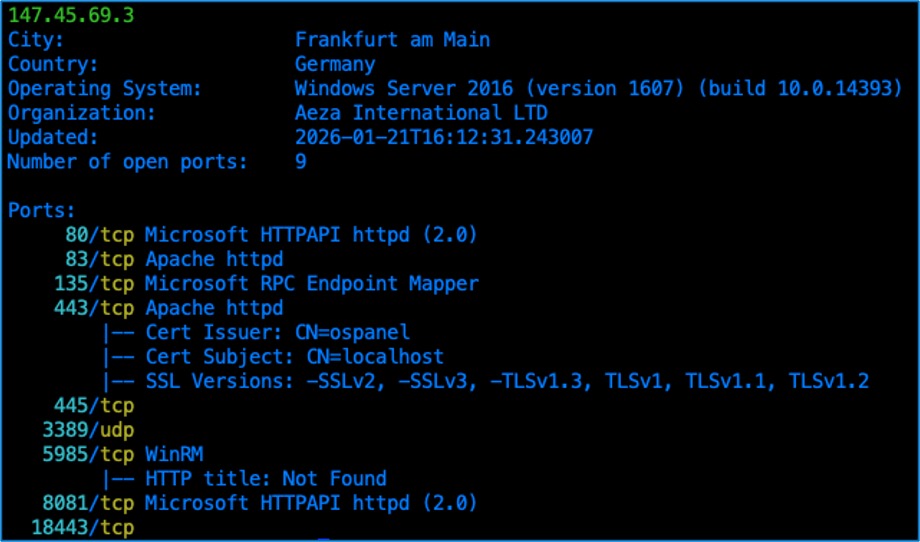

When a user’s browser connects to the altered IP address, e.g., 147.45.69.3, the device is fingerprinted and then directed to the next stage of the TDS if it passes the initial checks. This IP address serves as a proxy for the HTTP TDS, see Figure 3 for the host posture. Upon connection, a JavaScript file is returned that includes additional DNS queries which ensure that the connecting device is behind a compromised router. This is accomplished by including a URL with a domain name that should not resolve, e.g., gettranslate[.]ir. If the domain does not resolve, the script will redirect the user to www[.]google[.]com.

Figure 3. Host posture of TDS proxy (147.45.69.3) returned by the shadow DNS servers as of January 21, 2026

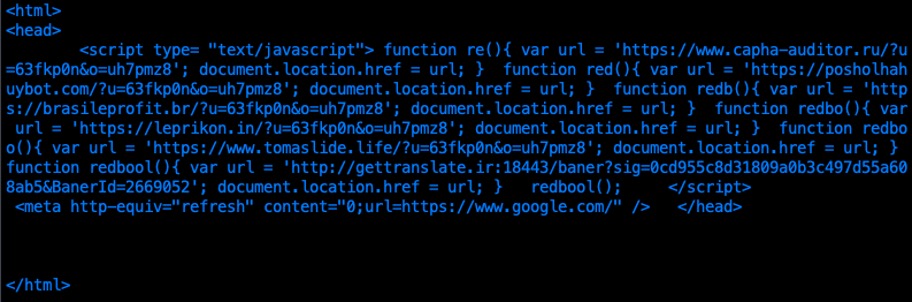

The script we analyzed contained seemingly old code, including URLs hosted on domains that were apparently never registered. See Figure 4. The purposes of the various functions re(), red(), redbo(), etc., are unknown. If the device is unable to resolve gettranslate[.]ir and connect on port 18443, it will do a refresh and load Google’s primary landing page. We have uncovered other versions of the scripts which use a different .ir domain.

Figure 4. Malicious script received in November 2025 through the Aeza TDS showing historical code using links on unregistered domains; the current function redbool() will attempt to connect to gettranslate[.]ir on port 18443.

If the first connection is successful, the device will be redirected again to another affiliate marketing platform link. From the URL

- http://gettranslate[.]ir:18443/baner?sig=ded8deb7ff580788cc58cbbf5508f3bf&BanerId=347333

we were redirected to an adtech TDS that we track via

- www.effectivegatecpm[.]com/bag4ni13i?key=cef13d2e5a9d1e200a50a6b3834cc7a9

From there, our traffic was resold and eventually we were shown various advertisements. But with all these checks in place to ensure the traffic is coming from the compromised routers, our browser would frequently end up at the requested site or redirected to Google.

We have found instances where directly visiting the TDS IP address resulted in an immediate redirection to a smartlink. For example, in the past, connecting to 89.208.107.49:8081 redirected to a smartlink using jackpotshop[.]life hosted in AS6898.

For reasons that are unclear, portions of the script were injected into comments in online forums, as well.

Impacts

In our research, the TDS always forced the browser into one of the two adtech platforms. But it is possible the threat actor is doing more with this system; the Reddit thread we uncovered indicated that bitcoin miners were installed and the admin was locked out.

While not overly sophisticated, the design of this TDS is clever and has a reasonable amount of infrastructure to maintain just to deliver unwanted advertising. And it’s clearly worked—this actor has operated undetected for years.

The Aeza shadow TDS we discovered harkens back to the days of DNSChanger malware, which was the work of an Estonian company. Distributed as software necessary to view videos on websites, the malware changed DNS configurations and served advertising content from the company. The FBI seized the C2 servers and indicted key figures in 2011.

Controlling DNS resolution is extremely powerful and goes well beyond the ability to deliver ads to a user. For example, a threat actor can selectively answer queries for critical services that are not protected by SSL certificates, or they can deny access to resources. The DNSChanger malware prevented antivirus updates on infected machines as a means of persistence.

More recently, ESET Research published findings on a Chinese actor who had tampered with DNS resolver settings and targeted software updates. The ability to determine when software is updated and to deliver modified updates can allow lateral movement within a network. Beyond these examples, DNS is used to discover services, check systems, establish trust, and connect to resources for every aspect of internet communication.

Overlay networks like this one can also impact DNS research because the false records get absorbed into some databases. There are many commercial sources for passive DNS available and some of these rely on “port 53” collection. In these cases, responses from authoritative name servers within the global DNS are mixed with the responses from alternate resolvers like the ones we’ve described here. If researchers aren’t aware of the type of DNS data they are using, they can draw false conclusions.

In our case, a third-party “port 53” collection helped us recognize this overlay network. There were Kimwolf botnet domains in that database, which resolved incorrectly to 89[.]208[.]107[.]49, an IP address we had already been monitoring for a few years. Independently, we had been “noodling” over mysterious DNS resolutions for domains like gettranslate[.]ir. Suddenly, we were able to put these two puzzles together and once we had the EDNS0 trick, the mystery quickly unraveled. How fun is that?